View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.

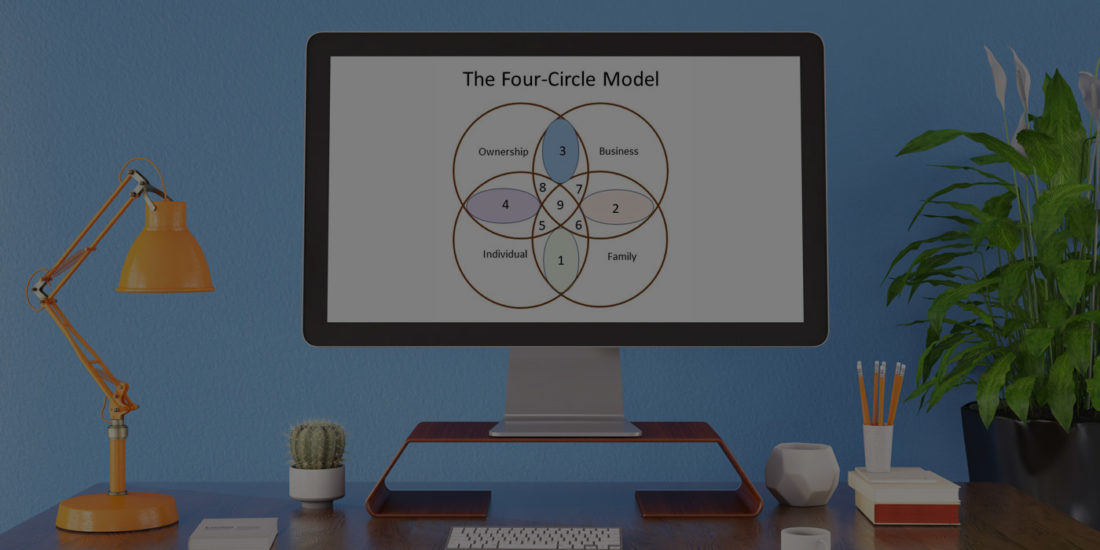

Thank you to this week’s contributors, Doug Gray and Natalie McVeigh, for their article that challenges practitioners’ reliance on bi-directional models that force “either-or” approaches to the complex issues confronting family enterprises. In the article, Doug and Natalie offer two models to address these inherent complexities and need to balance competing perspectives in family enterprises.

A recent meme declared 2020 as “The Year of Cataclysmic Change.” How about the changes in your client’s family business practice?

Our practices have evolved in 2020. We are more digitally connected, more collaborative, more responsive to client needs, and more generous than ever. In recent conversations we have defined two models that may be useful in your work with family business leaders. This short article describes the urgent need for using these, the “See-Saw” and “Double Helix” models, then suggests applications for you and your clients. We chose to express these models visually for two reasons: 1) approximately 50% of the brain processes visual information, and often when we see an image it helps us store and recall information more quickly than if we try to use words, and 2) use of images or metaphors helps our brains process information using bi-lateral functions from one side of the brain (e.g., the steady state with images we recognize) and the other side, like a change agent (e.g., processing new information into models that we already are familiar with).

Our experience is that bi-directional models are inaccurate and limited. For instance, the “Family Dilemma Question” implies that there is only one of two possible outcomes: either your client supports the “Family First” or the “Business First.” The logical fallacy of such either-or thinking does not accurately describe any family system that we have worked with. Dichotomous models ignore the complexity, the layers of collaboration, that abound in family systems. We need to discard bi-directional models as much as possible, because they limit the real complexity and dynamics in the family enterprises practitioners serve.

Instead, we are inclined to describe that complexity using two models. One model describes balancing a perspective, and one model describes how two seemingly dichotomous options may actually be part of the same phenomenon. We came to this conclusion during our most recent FFI G9 Virtual Study Group discussion, as we were reviewing an article by John Davis called “What Makes a Family Business Last?”. That article adopts two wonderful concepts of an Operator’s Mindset and an Owner’s Mindset. These are distinct mindsets, with characteristics, skills, and lenses that lead us into a lively discussion about applying “either-or” thinking. For instance, does one mindset come first? If so, then must we transition to the next mindset? As we were evaluating these questions, we realized that we began to use images and metaphors to visualize these two mindsets. We also realized that these two mindsets were not binary or mutually exclusive. For instance, we cannot imagine an operating company without both an operations mindset and an owner’s mindset. The images we used to describe these two mindsets lead us to think about how we describe the natural order in family systems.

The first model to express the complexity in family systems is the “See-Saw Model,” which may remind you of playground equipment in a primary school. Throughout the life cycle of every business, people balance between contrasting needs. One side is always higher than the other. People persist in or refrain from their behaviors based on the needs of other stakeholders at that time. Saying that one side has more value than the other side is not accurate and limits choice. Let’s consider as illustrations a few examples that were not addressed in Davis’s article.

Interdependence – Independence. Our clients often describe the tension of being an interdependent part of the family enterprise, as well as the desire to develop an independent dream. This is not an “either-or choice,” but a balance. A common question is, “How should a family member balance the desire for an independent career path with their interdependent role in the family council?”

Engagement – Exclusion. Many families describe the tension between the flexibility of younger leaders and the rigidity of older leaders, or the flexibility of a less structured business division and the rigidity of a more entrenched business division. We have also worked with clients who embrace flexibility in one division or geography, while maintaining rigidity in a different part of the business. So, what is the best balance?

Voice – Vote. Clients who lack governance or independent advisors may have a voice but may not have a vote. Their questions abound. If the next generation owners or spouses are not shareholders, then how important is their voice? Should an 18-year-old future owner have more of a voice than a more senior owner?

Bloodline – Talent. Most families struggle to balance bloodline and talent interests. That balance often leads to emotional questions. Should the family consider a non-family CEO, or develop the talent within the family? How long should the family retain a mediocre manager who is a family member if that manager’s division is struggling?

We thought these four illustrations would help other practitioners and their clients adapt to change. We always balance multiple interests. You may know that 50% of our genes are templates (i.e., they do not change during our lifetimes) and the other 50% are transcription, (i.e., they change through our lifetime and they change more when we talk to one another.) As Judith Glaser said, “Words create worlds.” We can all use the See-Saw Model to help our clients co-create changes in their family system for generations.

The second model to describe the complexity of change in 2020 (and beyond) is the “Double Helix Model.” Let’s make this simple: take the image below. Then add two labels for your family business. The labels could be used to describe ongoing links between core business needs (e.g., legacy and profitability, current clients and future clients) or core values (e.g., hope for a better future and accepting the complex current reality, rewarding ethical behavior and punishing unethical behavior). The point is that all life forms are comprised of DNA. The structure of DNA is a double helix. Why use any other image to describe the natural patterns in your family business?

In molecular genetics, a DNA molecule consists of two strands that wind around each other like a twisted ladder or a spiral staircase. In a family business, each strand is comprised of alternating influences of family values, legacy and business decisions, and daily management of the company. The ties between these strands may include succession, leadership, governance, valuation, technology, philanthropy, ownership, and so on. Over time, the ties that bind us become stronger when reinforced.

Natural patterns are prevalent in family systems. To paraphrase Peter Senge (1990), learning organizations adapt when they use new mental models to share visions as teams that reinforce personal mastery. A G4 family business owner, Adam Fleischer, said it better, “I’ve found that it’s really important to stay true to who you are and identify your company’s culture and build people that fit that culture.” In his example, Label 1 would be “company culture” and Label 2 would be “people.” The ties that bind include “staying true to who you are, hiring carefully, rewarding desired behavior, firing people who don’t fit.”

We hope these See-Saw or Double Helix models will prove useful in your work with family businesses. To summarize their benefits:

- Bi-directional models that force either-or thinking limit our responses to change. When we embrace multiple perspectives, then we learn new solutions to old problems.

- Teams are stronger than individuals. Networks of teams can be developed and must be nurtured. How you collaborate in 2021 and beyond will be critical to your future.

- We have more global access to evidence-based models than ever in human history. Learning agility is a measure of your response to change.

- Change is complex and each family system is unique. There is a spectrum of functioning in any family enterprise. We recommend reinforcing what is working (strengths) and modifying what is not (weaknesses).

- Practitioners have always attempted to demonstrate agility, collaboration, and resilience in response to threats. The pace of change in 2021 will be faster than it is today.

References

Davis, J.A. (2020). “What Makes a Family Business Last?” Harvard Business Review; Boston.

Senge, P.M. (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The art and practice of the Learning Organization. Doubleday; New York.

About the Contributor

Doug Gray, PhD, PCC has always focused on outcome-based leader development. He has worked with over 10,000 leaders in multiple business sectors, schools and colleges, families and non-profits. Doug is a consultant with the Family Business Consulting Group, and a member of FFI. Doug is the author of “Objectives + Key Results (OKR) Leadership; How to Apply Silicon Valley’s Secret Sauce to Your Career, Team or Organization.” He can be reached at doug@action-learning.com.

Doug Gray, PhD, PCC has always focused on outcome-based leader development. He has worked with over 10,000 leaders in multiple business sectors, schools and colleges, families and non-profits. Doug is a consultant with the Family Business Consulting Group, and a member of FFI. Doug is the author of “Objectives + Key Results (OKR) Leadership; How to Apply Silicon Valley’s Secret Sauce to Your Career, Team or Organization.” He can be reached at doug@action-learning.com.

Natalie McVeigh, ACFWA, ACFBA, a consultant and coach with EisnerAmper in their Center for Individual and Organizational Performance. In addition to her work with clients and teaching, she is the chair of FFI’s Next Gen Practitioners Virtual Study Group and is a member of FFI’s Board of Directors. Natalie is also a member of the GEN faculty. Natalie can be reached at natalie.mcveigh@eisneramper.com.

Natalie McVeigh, ACFWA, ACFBA, a consultant and coach with EisnerAmper in their Center for Individual and Organizational Performance. In addition to her work with clients and teaching, she is the chair of FFI’s Next Gen Practitioners Virtual Study Group and is a member of FFI’s Board of Directors. Natalie is also a member of the GEN faculty. Natalie can be reached at natalie.mcveigh@eisneramper.com.

View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.