View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.

In this week’s edition of FFI Practitioner, Ricardo Mejía shares his reflections on the importance of storytelling as a way to transmit the “company soul” to the next generation of family owners.

William Clay Ford Jr., executive chair of Ford Motor Company, former president, CEO, COO of Ford, and a fourth-generation member of this prestigious family, once said that he does not know if a company can have a soul—but that he would like to think it can.1

And if so, he hoped that Ford’s would be an “old soul,” with the history and values that phrase implies.

Here are a few examples that exemplify Mr. Ford’s notion of a company soul.

The Soul of a Company

I met León Rosas (fictitious name) many years ago. He was born in one of the poorest regions of Colombia, in an inhospitable land and climate. When he was 15 years old, he moved to Medellín, where after many misfortunes he was able to study accounting at the SENA (Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje, or National Training Service, in Colombia). After graduation he got a job as an accountant in a small firm. A few years later he got married and bought his wife a sewing machine. Every afternoon, once he left his work, he would run around the city selling the garments his wife had spent hours sewing.

Today, his company has annual revenues of US $150 million, but he is not primarily interested in profits alone. Instead, his main motivation is to grow the company to create more jobs and help the children of his workers study and improve their standard of living, as he had earlier in his own life.

That is the soul of his company.

The Soul of a Country

At the beginning of the 19th century, when the United States began to expand westward, the Indiana cabin of Abraham Lincoln’s father, Thomas, was a popular stop for those traveling to settle in the new territories. Without television, radio, or newspapers, the nights by the fire revolved around each other’s stories and tales. Thomas Lincoln was reportedly outstanding at dazzling his audience with his stories, a trait that his son Abraham would inherit.2 Although the future US president did not understand many of his father’s curious tales, he memorized them and later tried to find their meaning. Thus, from a young age he developed an ability to tell stories that helped him win the affection of the people and reach the presidency in one of the most difficult moments in US history. Through his storytelling, Lincoln was trying to transmit a soul to his country.

Reflections on Souls and Companies

If we understand the word “soul” as the set of values that define behavior, then companies, like human beings, can and maybe should have souls. However a business leader creates a soul in a company, I suggest that this development will depend largely on the training and education received by the owners. Given that family businesses represent a significant portion of the global economy (it’s generally accepted that family-owned businesses constitute anywhere between 50% and 90% of the world’s GDP) the soul of these companies will largely depend on the culture of the family owners and the owners’ ability to transmit that culture to the heirs and into the business.

Storytelling in Family Enterprises

Just as stories have been transmitted orally for millennia, so too should the culture of the founder of a company. According to Elizabeth Stone,3 families that control companies must practice telling stories. No matter how successful the business strategies, how effective the administrative structure, how successful the management team, if the families do not share their stories and histories, future generations will grow up without the memory that can help build a collective identity.

To achieve this collective identity, Stone recommends transmitting the main cultural values from generation to generation. When family members learn to tell their stories and have fun telling the main anecdotes and values that constitute their roots, shareholders, managers, and employees will learn of their commitment to the family business and to society.

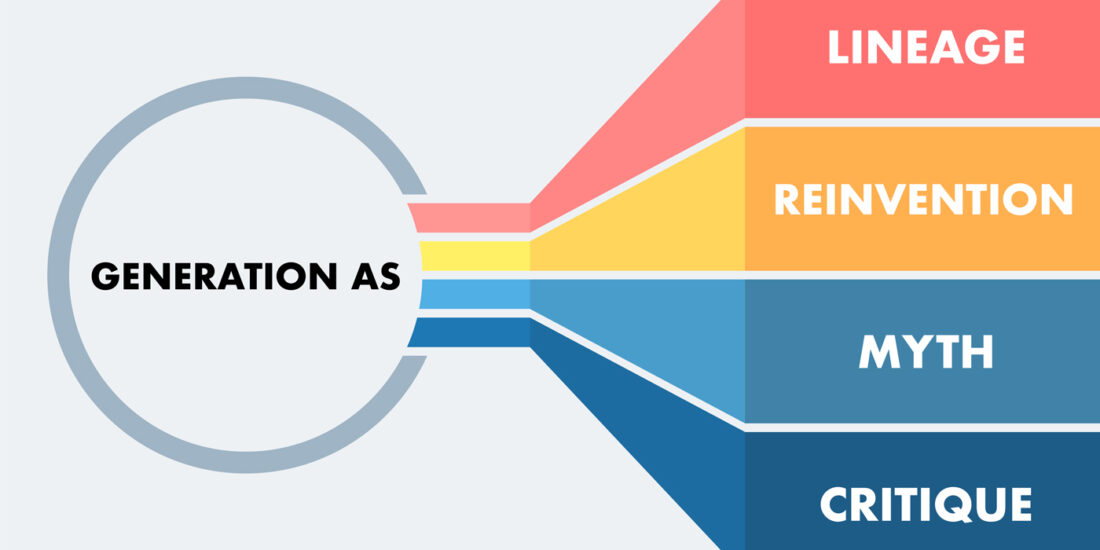

The stories may even include a mix of fact and fiction, preserving special themes and events and highlighting the most important personalities in the family. Stories convey, in a fanciful way, various myths, facts, and the most important aspects of the history of the family and the company.

According to Stone, family gatherings around special events are a great opportunity to tell stories. She adds, however, that the dissemination of family values through print or videos, although important, are not enough unless they are accompanied by oral transmission.

To what extent does the disintegration of some second- and third-generation family businesses lie in the inability to adequately engage these generations of family members and the business leaders and employees? To instill in them a soul? In the generational transition, one of the most important responsibilities of elders is to educate the next generations to be good shareholders. Teach them to dream together how to grow the family legacy, not just for the benefit of the family, but for society in general.

In his 2010 Nobel Lecture, novelist Mario Vargas Llosa described how novels helped to transport him to an imaginary world, without the defects of the real one.4 It is the way in which readers escape from the problems of everyday life and travel to a fascinating and unknown world, often where life and the environment are much better.

Just as Jules Verne launched the world into the conquest of space and the oceans with stories, entrepreneurs and managers can create stories that invite dreams of a better world, with new products, new markets, new channels, new regions, new technologies, and much more. In other words, adding soul to their companies.

Not only poets and novelists are entitled to dream. Entrepreneurs and managers can too.

References

1 Sherrill, Martha. “The Buddha of Detroit,” New York Times Magazine, November 26, 2000. Accessed February 28, 2024, via https://www.nytimes.com/2000/11/26/magazine/the-buddha-of-detroit.html.

2 “Thomas Lincoln,” National Park Service, accessed February 28, 2024, via https://www.nps.gov/people/thomas-lincoln.htm

3 Stone, Elizabeth. “Stories Make a Family,” New York Times Magazine, January 24, 1988. Accessed February 28, 2024, via https://www.nytimes.com/1988/01/24/magazine/stories-make-a-family.html.

4 Llosa, Mario Vargas, trans. Edith Grossman. Mario Vargas Llosa – Nobel Lecture. Accessed February 28, 2024, via https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2010/vargas_llosa/lecture/.

About the Contributor

Ricardo Mejía, CFBA, CFWA, is a former FFI board member. After a long career as manager in public and family-owned companies, he developed extensive experience in corporate governance, strategy, and KPI management. He has been professor in the management programs at Universidad de Los Andes and Universidad EAFIT, is a contributor to several Colombian newspapers, and is frequently invited as lecturer in national forums. Ricardo can be reached at ricardom@sdj.com.co.

View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.