View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.

Continuing our series on Time, we are pleased to present an article by Joseph Astrachan and Claudia Binz Astrachan. In this article, they discuss how to think about urgency from a risk perspective and provide an Urgency-Cost Framework grid for advisors that illustrates how to help client families identify and address different types of decision-making during the consulting process.

“A system that can evolve can survive almost any change by changing itself.”1 At the same time, too much or ill-timed change can bring a system down. Furthermore, any system includes elements that are locked into their current state unless other system elements change first—and some cannot be changed no matter what. It is essential for any family enterprise advisor to understand what can and cannot be changed, as well as the conditions that change is contingent on, the right time to make a change, and the right amount and pace of change.

Time is a crucial concept in the context of change, and when working with families, consultants likely do not always pay enough attention to it. Over the years, consultants and family members have underestimated more than a few times how long it might take to get a family’s buy-in for a seemingly simple governance policy, or how quickly a strained relationship might heal. Not just that, consultants have also succumbed to the false sense of urgency that can drive a family to rush through a process—even when it was clear that it was not an emergency and that a slower process might have allowed for more deliberation and inclusion.

This article offers several observations around time, change, and the sense of urgency, and contextualizes those relationships in a simple and hopefully useful framework.

True Urgency: Overestimated and Overlooked

When one of the first questions a family asks at the beginning of an engagement is a variation of “How long will this take?” consultants are well-advised to check whether the family is suffering from a false sense of urgency. While some matters need to be addressed and resolved swiftly, most issues are either not as urgent or will require a lot of time for deliberation and careful management of family conflict. Properly attributing and communicating the level of urgency as well as the timeframe for change, and possibly resolution, will set up both the consulting engagement and the family for success.

False urgency presents a decision-making paradox. On the one hand, false urgency can make one feel compelled to rush through topics that create anxiety or pose an uncomfortable conflict. On the other hand, the feeling of running out of time is an added stressor that not only limits what may be considered possible but also inhibits the ability to think calmly and rationally. When time is limited, options appear to be limited as well, and impulsive decisions designed to “just make the problem go away” are all the more likely.

Example #1

Take, for example, the need for an employment policy. While developing a family employment policy early can save future conflict, one family client decided that the conversations would be too difficult and that the many issues raised would lead to family conflict. Therefore, they waited until the eldest child of the next generation was graduating their university studies. At that moment, that child’s branch insisted there was not enough time to develop a well-constructed and widely-accepted policy. That branch badgered and coerced the others into accepting a very open policy of hiring any family member who wanted a job. As could be expected, this led feelings of favoritism and mistrust in the family and perceptions of nepotism among the workforce.

People are generally predisposed to believing that it is essential to find the right time to discuss or even consider something that might require a large change or a difficult conversation (e.g., marriage, having children, business succession). This anxiety can cause procrastination around planning for difficult tasks such as leadership and ownership transitions, significant business investments and acquisitions, and responding to a negative business environment through actions such as divestitures or layoffs. This procrastination leaves even less time and increases the pressure around these most feared tasks, which further limits possibilities and the ability to properly prepare—which further justifies fear.

A client once shared that a mentor had encouraged her “to run to the hard stuff” in order to be challenged and to grow. This is an incredibly valuable mindset in this particular context. Running towards difficult and unavoidable decisions as soon as possible maximizes possibilities and the planning timeframe available. Consistently practicing this allows a family to exercise this important muscle.

Example #2

A family client had experienced significant hardships, including unexpected deaths of children and spouses. Perhaps because of these experiences, they found the strength to deal with difficult conversations around developing a cohesive blended family, buying out disgruntled family members, designing a family governance system, and developing a family educational program years before the second generation graduated high school. They had ample time to consider the ideas, issues, conflicts, and potential negative consequences of one or another course of action, which allowed them to be ready and united when the next generation was ready to enter the enterprise. It even seemed like they were better prepared to contend with unexpected crises owing to having had a wealth of practice in confronting difficult and emotionally intense conversations.

Urgency-Cost Tradeoffs: A Framework

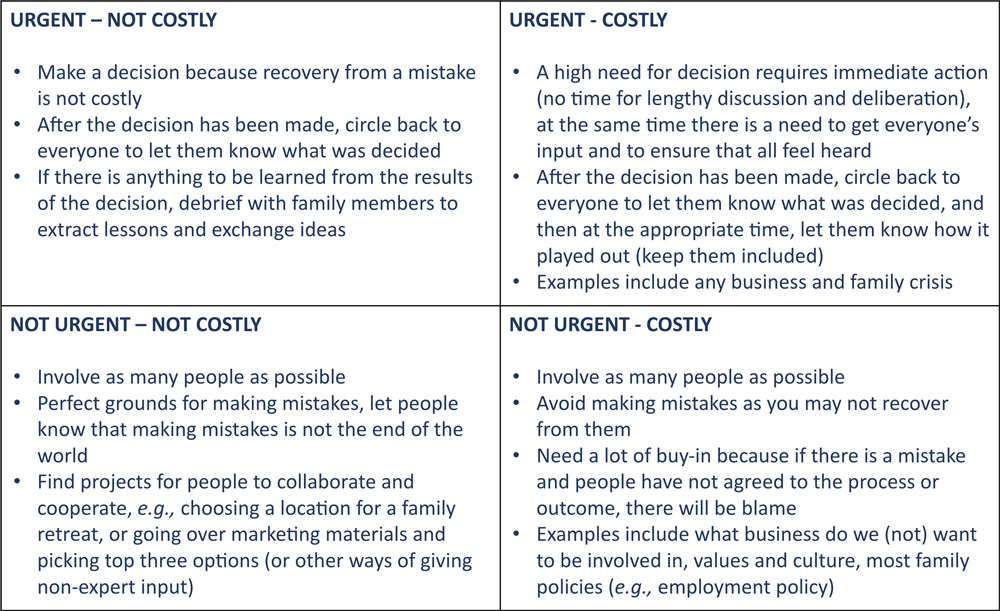

All decisions have an element of urgency – ranging from a complete lack thereof to immediate reaction required – and the cost associated with a decision failure or the cost to recover from a specific decision.2

In general, decisions that are not costly, whether urgent or not, are good training grounds for individuals or groups to learn how to make decisions effectively. Since the cost of a bad decision is low, and mistakes can be easily rectified, decision practice in these situations has a relatively low tuition. Decisions that are not urgent, whether costly or not, allow more time for deliberation, for more data to be collected, and for more consequences to be considered. Decisions can be checked with others and provide educational opportunities for younger individuals and groups.

Before looking at the intersections of these two dimensions, it is important to highlight that nonurgent decisions often go ignored until they become urgent. In a world of infinite decisions that “need” to be made, those that are not urgent can be first delegated to others, at least for the development of options. Decisions that are neither urgent nor costly can be fully delegated. Delegation allows for inclusion of other voices and frees up the more experienced decision makers to focus their energies on more pressing issues.

Figure 1: The Urgency-Cost Framework

In the bottom right corner of the Urgency-Cost Framework (Figure 1) are decisions that are not urgent, but the cost of a bad decision is significant. This includes things like developing a long-term enterprise strategy, values, and an accepted single version of a family history. It also might include things like a dividend policy, family meetings and governance, or a liquidity policy, as well as business issues like changing a pricing policy, developing and upgrading a board of directors, or selecting new vendors. While decision processes should not be delayed, it is often crucial to gain as wide and strong a commitment to a decision as possible. This effective decision-making process can build unity, reduce post-decision regret,3 (Janis & Mann, 1976), and reduce the chances of blame dynamics if the decision yields negative consequences, which consequently speeds up recovery from bad decisions. One way to assure widespread strong commitment is to be very inclusive in terms of who is involved in and gets to vote on a decision.

The bottom left describes decisions that are neither costly nor urgent. In general, obtaining buy-in from a large group is less important for these decisions. Because the decisions are not urgent, there is time for a mentor or others to review the decision-making and help the decision maker learn, grow, and develop.

In the upper left quadrant are decisions that are urgent but not costly. Widespread buy-in is not important, so group decision-making is not essential. It is likely fine to make decisions and report on the decision made to a larger group afterwards.

The upper right quadrant may be the trickiest, as decisions need to be made in a hurry and the cost of recovering from a bad decision is significant. The need for a quick decision means group decision-making is not feasible. However, the cost of the decision means that buy-in is still important. One recommended course of action is to get as many opinions as possible and then decide in a timely fashion. After the decision has been made, the decision maker should explain why the decision was made to as many people as possible to help with buy-in. Widespread participation in urgent decision-making is not a wise idea as it slows decisions.

Conclusion

Once a problem is recognized, most people with busy lives and constant and competing demands for their attention want to resolve the issue as expediently as possible. Many fall into urgency mode, even if an immediate response would not solve problem at hand. Consultants sometimes enable clients’ misguided sense of urgency by putting an ambitious roadmap and timeline in place, seemingly supporting clients in what they seem to want most: the swift resolution of an issue that plagues them.

Setting clients up for success means giving them a realistic timeline upon which their objectives can unfold. This timeline takes into consideration how much change can be reasonably achieved within the constraints of the system and is not driven by the family’s wishful thinking or the consultants’ own biases and desires.

1 Meadows, Thinking in Systems, 159.

2 Those who serve on corporate boards will recognize this as a derivation of the cost of a risk and the probability of a risk happening that guides the focus of board risk and compliance committees.

3 Janis and Mann, “Coping with Decisional Conflict,” 666.

References

Janis, Irving L., and Leon Mann. (1976). “Coping with Decisional Conflict: An Analysis of How Stress Affects Decision-Making Suggests Interventions to Improve the Process.” American Scientist, 64, no. 6 (1976): 657-667.

Meadows, Donella H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2008.

About the Contributor

Joseph H. Astrachan, FFI Fellow, is Board chair and founder of Generation6, Emeritus Professor of Management and Entrepreneurship at Kennesaw State University, Family Business Fellow with the Smith Family Business Initiative at Cornell University, visiting scholar at Germany’s Witten/Herdecke University, the Institut für Finanzdienstleistungen, Luzern Switzerland, and Affiliated Professor at the Centre for Family Entrepreneurship and Ownership at Sweden’s Jönköping International Business School. He has received the FFI Richard Beckhard Practice Award and the FFI International Award and is a former editor of Family Business Review. He can be reached at jastrachan@generation6.com.

Claudia Binz Astrachan, PhD, researcher and lecturer at Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts, is the head of the governance practice at Generation6, a family business consulting company, and serves on the board of IFERA. Her scientific contributions have been published in peer-reviewed journals, practice-oriented journals, and research reports for the family business community. She can be reached at castrachan@generation6.com.

View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.