View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.

This week, we are pleased to continue our series of commentaries on “Professionalizing the Business Family: The Five Pillars of Competent, Committed and Sustainable Ownership” – a research report supported by the FFI 2086 Society. Thank you to report authors Fabian Bernhard and Torsten Pieper, who are joined by FFI Fellow Greg McCann, for this article focusing on how advisors can help next-generation owners develop self-competencies.

The research report “Professionalizing the Family Business” extensively discusses the key elements necessary to be a competent owner of a family business. In this commentary we aim to expand on the report’s findings in regard to the question, “How can family business advisors help prepare the next generation to gain self-competencies?” In doing so, we point out that the preparation of the next-generation owners encompasses both internal and external aspects, and aligning them is key to effective development of owners’ competencies.

Preparing successors is an evolutionary process that requires more than cognitive learning

While most formal education that next gens undergo focuses on teaching the “hard skills” about how to run a business, too little attention is often paid to “soft skills.” However, this particular form of personal development can be especially important to increase the chances of becoming a competent owner of a family business. In particular, these softer competencies which are relevant to the complexity found in family businesses can become a crucial element. They are important to the establishment of positive family dynamics, and ultimately of a shared vision between generations. Thus, preparing the next-generation owners with necessary self-competencies must be a holistic endeavor.

Even beyond the business sphere, the family may be interested in lifelong holistic development of the next generation. A future owner with a solid self-esteem—defined as honest and healthy evaluation of her or his own self-worth—is more able to trust her or his own judgment, to care for others, and to engage in difficult discussions more effectively (Astrachan & Pieper, 2011).

Self-reflection and gaining self-awareness

Raised in a potentially nepotistic environment, next gens often benefit from advantages that others do not have. For example, growing up in a successful family business can lead to an inherent understanding of entitlement to wealth and an automatic role in the family business. Additionally, such perceptions can extend beyond the direct business environment. For example, a next-generation member one author worked with was pulled over for speeding and the police officer said: “I can’t give you a ticket in this town” (because of the individual’s family’s business and its prominence in the community).

While being a member of the next-generation in a family business can represent a great opportunity, such privileges can reduce next gens’ motivation to explore and establish who they are as individuals—leading to complacency and impeding their personal growth (Miller et al., 2003). Especially in the complex world of family businesses, with its overlapping influences of the family system and the business system, a self-competent owner knows where he or she comes from, his or her position in the family and the business, and finally, where to go from there. Strong feelings of entitlement, however, bear the risk of eroding one’s credibility.

Credibility consists of two related aspects:

- Internal credibility: legitimate self-confidence in your role, related to self-esteem; and

- External credibility: legitimate validation by relevant people and stakeholders of the family business

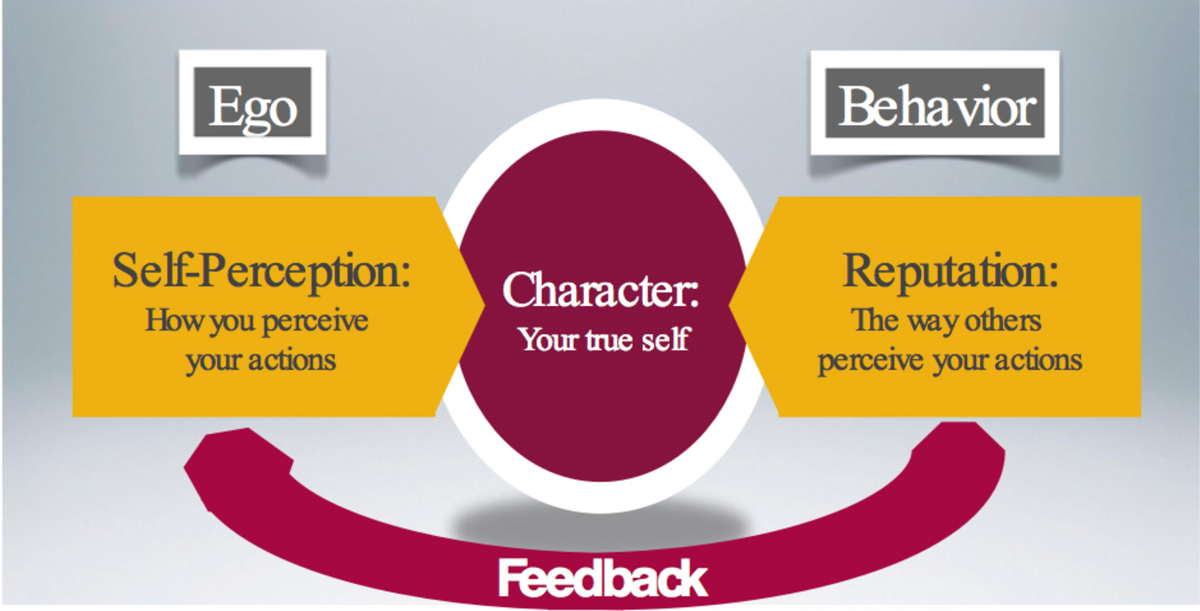

Receiving accurate, objective feedback, initially from one’s parents, is vital to developing one’s self-esteem and aligning the internal self-perception of one’s character with the external perception (i.e., how others see us, termed “reputation” in Figure 1). If this feedback is lacking (and it often can be lacking in successful family businesses), it is analogous to driving a car with the dashboard covered; the driver is at far greater risk to derail.

As the graphic below shows, accurate feedback helps to align these two aspects.

Character/Self-esteem

Adapted from Who Do You Think You Are? by Greg McCann page 3.

Advisors’ role in developing self-competent owners

Family business advisors can assist next gens by supporting a reflection on behavioral patterns in their family and themselves. By using tools related to genealogy, identification of one’s values and beliefs, or personal career- and goal-setting exercises, advisors help young next gens develop greater self-awareness. Deepening this awareness can be done in many ways, including meditation, white space for reflecting, exploration of family history, or even seeking a mentor or coach. At the core is the ability to pause and step back from a system, be that your own ego, your family, the business, the industry, or even your culture, and to see it more objectively and be less attached to your narrative as inherent truth.

Common tools to foster self-reflection and to gain self-awareness are regularly described in the literature (e.g., Barbera et al., 2015; Jaffe, 1990; McCann, 2007), and they include the following elements:

- Learning more about one’s values and how one defines one’s “personal success.” A values-based definition of success gives next gens the ability to take ownership of their career and of what they want, and not have others write their scripts for them.

- Writing one’s life plan (i.e., prioritizing personal goals with respect to one’s career, family life, etc.). We have seen dozens of next-generation family members build their self-esteem through a deep dive into self-awareness, aggressively seeking feedback and achieving greater alignment that this process enables.

- Learning about the family’s past and hidden dynamics by means of genograms. A three-generation exploration of patterns, conflict, and relationships can deepen one’s understanding of their family system.

- Learning about the business’s past and hidden dynamics by conducting interviews with other family members.

- Personality tests (e.g., MBTI, Big Five). These tools tend to normalize and validate one’s strengths and weaknesses, and they uncover blind spots. For example, one of the sixteen MBTI types, ENFJ, tends to be responsible but poor on details and can be perceived as overly critical of upper management. These are all traits worth bringing into awareness.

- Practicing giving, but also receiving, feedback.

Developing these competencies is, however, not a once-in-a-lifetime exercise. It can be seen analogously to getting in shape, which is an ongoing process that requires commitment and endurance. To extend the analogy, if you aren’t sweating or stretching, it is not much of a workout. Despite these efforts, gaining self-awareness is an essential starting point. After all, you cannot build on a strength, navigate a weakness, or take ownership for a blind spot until you become aware of it. Deeping your awareness is thus step one.

Normalization and validation

A second step is a process commonly described as “normalization.” Even though each family business is unique, some challenges are similar across firms and families. Young members of family businesses often feel left alone with problems which they believe to be exceptional to their situation. Advisors can help by encouraging next gens to observe, understand, and learn from others in similar situations within their peer group. Related techniques include advisors serving as mentors who enable insights into typical challenges in family businesses. By using normalization techniques, struggling family members can realize that these challenges are not unique to their case, but are normal among people in their situation. Building on this realization, next gens can then further develop self-awareness and identify their strengths, weaknesses, and relationships in the family and in the business environment.

Effective communication

A third aspect related to preparing effective owners is the quality of communication. Particularly, family businesses face challenges when it comes to openly discussing controversial topics, such as succession, wealth, money, and familial conflict. Advisors can stimulate, coach, and offer practice opportunities for candid and profound communication between family members. Advisors are in a position to encourage conversation and help to overcome deadlocks in communication during difficult times.

Developing a culture that gives and receives feedback, even if it temporarily threatens family harmony, is a crucial step. By assisting next gens in the ways to openly discuss and question family decisions, advisors can play an important role in developing self-competencies in young owners that shall benefit the family, the business, and stakeholders in the long run.

References

- Astrachan, J. H., & Pieper, T. M. (2011). Developing responsible owners in family business. In EQUA-Stiftung (Ed.): Gesellschafterkompetenz – Die Verantwortung der Eigentümer von Familienunternehmen. EQUA Schriftenreihe, Band 10/2011. Bonn: Unternehmer Medien GmbH, pp. 102-110.

- Barbera, F., Bernhard, F., Nacht, J., & McCann, G. (2015). The Relevance of a Whole-Person Learning Approach to Family Business Education: Concepts, Evidence and Implications. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 14(3), 322-346.

- Jaffe, DT. (1990). Working with the ones you love: Conflict resolution & problem solving strategies for a successful family business: Conari Press.

- McCann. (2007). When your parents sign the paychecks: Finding career success inside or outside the family business: JIST.

- Miller, D., Steier, L., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2003). Lost in time: Intergenerational succession, change, and failure in family business. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(4), 513-531.

About the Contributors

Fabian Bernhard, PhD, is an associate professor of family business and part of the Family Business Center at EDHEC Business School in Paris, Lille, and London. He is also a research fellow for family business at the University of Mannheim in Germany and previously was at Stetson University in Florida. He is the recipient of several honors and awards for his work, including the 2011 FFI Best Doctoral Dissertation Honorable Mention for “Psychological Ownership in Family Businesses,” which was later published in book form. He is a member of the FFI board of directors, and since 2014 he has been serving on the editorial review board of the Family Business Review (FBR).

Greg McCann has been coaching for over 20 years within his roles as the founder and director of Stetson University’s Family Enterprise Center, director of its executive MBA, as a consultant and coach in his firm, McCann & Associates. He has had several coaches throughout his career. He is an FFI Fellow and a former member of the FFI board of directors.

Torsten M. Pieper is Associate Professor of Management in the Belk College of Business at The University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Dr. Pieper is President of the International Family Enterprise Research Academy (IFERA), the largest network association of family business researchers in the world, and Editor-in-Chief of the Elsevier title Journal of Family Business Strategy (JFBS). His research and writings have been recognized with numerous national and international awards.

View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.