View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.

This week we are pleased to continue our series of commentaries on the report, sponsored by the FFI 2086 Society, entitled “The Governance Marathon: Dynamic Durability in Entrepreneurial Families Amid Disruptions.” Thank you to Marta Widz and Maria José Parada for their article that builds upon the report’s key takeaways to include the importance of developing the family business group’s identity to foster dynamic durability in the governance systems.

Nurturing Dynamic Durability in Entrepreneurial Families

The recent research report sponsored by the FFI 2086 Society, “The Governance Marathon: Dynamic durability in entrepreneurial families amid disruptions,” approaches the idea that governance is a socio-technical system and thus susceptible to external and internal changes.

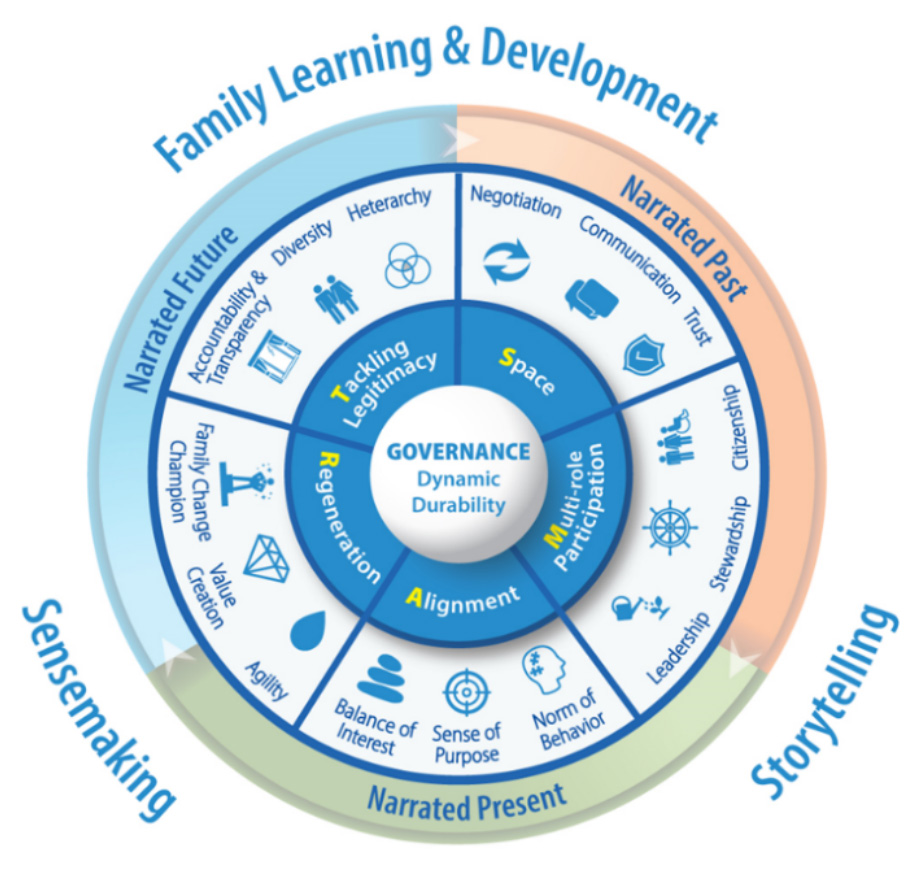

It proposes the G-SMART1 model with three overarching social processes (sensemaking, storytelling, and family learning and development) framing five social dimensions (space, multi-role participation, alignment, regeneration, and tackling legitimacy), as well as “meta-governance”—awareness of the governance system—which are all necessary for nurturing dynamic durability in entrepreneurial families (Figure 1).

Figure 1: G-SMART Model of Dynamic Durability2

While the report authors assert that the governance is a social practice, they do not include another component of social process: the development of collective business family identity and meta-identity.

Collective Business Family Identity

Social identity theory asserts that identity emerges from the contemplation of commonly asked questions about who we are and where we belong.3,4 Individual identity reflects the social context of a particular individual who aligns his or her behavior to attributes, norms, and customs of a social group based on the need of belonging.5,6,7,8 Similarly, organizational identity, a type of collective identity, is related to “who we are” as an organization and is also socially constructed.9,10,11 It emerges from continued interaction among organizational stakeholders and the “interchange between internal and external definitions of the organization.”12

Collective business family identity is a complex and dynamic phenomenon. The complexity comes from the overlap of multiple social systems, which leads to the development of multiple identities by individuals and causes role conflicts. For example, a family business owner would typically develop identities as a businessperson, a family member, and an owner at the same time.13

Generational transition pulls the business family members away from founder identity, which cultivates the heroic entrepreneurial narrative, and from legacy business centric identity, which cultivates the single narrative of “us” as members of the legacy business exclusively. Building a Family Business Group (FBG) identity requires forming collective family identity and integration of the investor’s identity14 with the owner’s identity15 of an enterprising family and its organizational identities.

Integrating Family Business Group (FBG) Identity into the G-SMART Model of Dynamic Durability

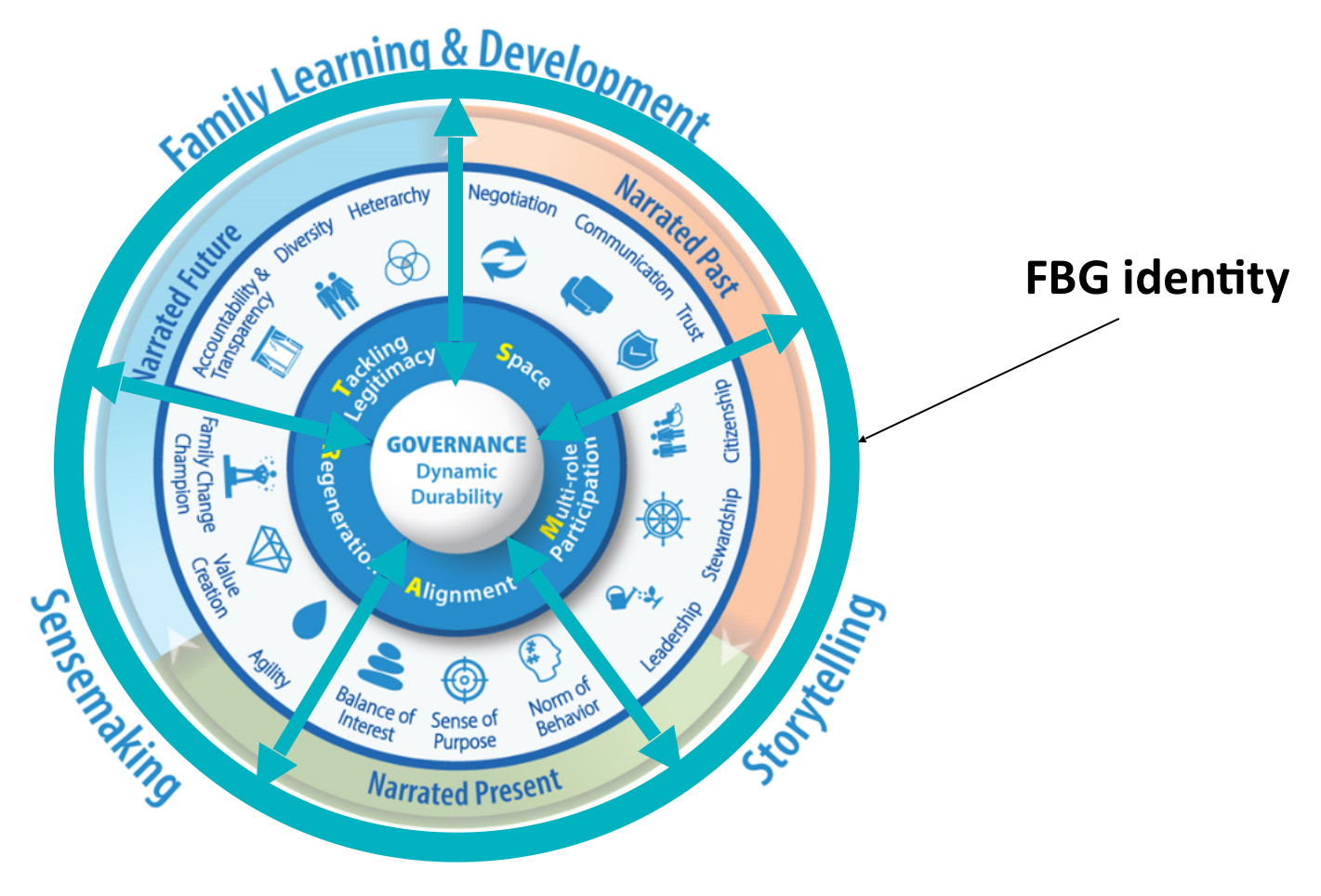

FBG identity development is based on identity negotiations, which take place in the form of ongoing social interactions and results in a regeneration of the identity, an alignment of multi-role narratives, storytelling, and sensemaking…that is, the constituent elements of the G-SMART model!

Based on this understanding of governance as a social practice, we propose to extend the dynamic durability model by framing it within the concept of an FBG identity (Figure 2).

Figure 2. G-SMART Model of Dynamic Durability Integrating the Family Business Group Identity

Like a rim and spokes that keep a wheel together, identity keeps the governance together. Based on this continuous, reciprocal action, identity interacts with governance.

Lessons for Advisors on Meta-Identity

Change is constant. Dynamic durability recognizes that and amplifies the importance of self-reflection within the governance system and conscious governing of the governance system itself, i.e., meta-governance. Identity that fails to reflect the current state of affairs may result in improper governance. For example, a family business group that cultivates a “single family-single business” identity, despite owning a diverse portfolio of businesses, may allocate resources predominantly to the legacy business or refrain from appointing family members to the boards of businesses other than the legacy businesses–regardless of the size of the legacy business in relation to the overall business portfolio.

Key Questions for Advisors

Meta-identity is necessary for a business family to attain dynamic durability, and advisors can foster it by asking themselves these key questions:

- How aware are you as an advisor that the collective identity of a business family and the collective identity of the organization are important catalysts of the governance dynamics?

- As an advisor, can you integrate identity and meta-identity in your work with family enterprise clients?

- What could be potential consequences, positive or negative, to the governance system when FBG identity is not included?

Recommendations for Advisors to Help Foster Clients’ Meta-Identity

Below we offer a suggested process to help guide advisors as they assist business families in fostering their meta-identity.

Wishing you an interesting journey integrating identity in the dynamic and durable governance system.

- Define the current stage of development of the business family: Owner Firm, Sibling Partnership, Cousin Consortium, Family Office, etc., and understand the composition of the asset portfolio and the role of the legacy business.

- Examine the individual identities of key family members and key organization members and explore how identity conflicts may impact the collective family and organizational identities.

- Explore the family collective identity as well as the organizational identity. Investigate what role the founder’s narrative plays into the self-identity of the family and the organization.

- Investigate how collective identity is signaled. What stories are told and not told? Who facilitates the storytelling and sensemaking? In what way is the collective identity of the next generation different compared to the collective identity of current generation, and what does that tell you?

- Explore disparities between the family’s collective self-identity and the identity signaled to the external stakeholders. Interview stakeholders other than family members, such as non-family employees, suppliers, and customers.

- Assist the business family to build a coherent collective identity that reflects the family business group’s current status.

- Allow different voices to emerge and different family members to participate in the process of developing a collective identity, as well as to question the previous identity, build on it, and reframe it based on new events. Build stories around the events that happen over time. Facilitate family identity negotiations, if necessary.

- Design and run family learning & development sessions that would integrate the collective identity dynamics and developments, and would foster self-reflection and meta-identity.

- Integrate the collective identity and meta-identity as part of the dynamic durability in the governance and meta-governance. See how evolving identity influences the evolving governance and vice-versa.

- Raise awareness of the necessity to adapt the collective identity periodically. Revisit it at least after any major change that takes place on the family or business side.

References

1G denotes Governance and SMART specifies the five building blocks of Dynamic Durability, namely (i) Space, (ii) Multi-Role Participation, (iii) Alignment, (iv) Regeneration, and (v) Tackling Legitimacy.

2Cheng, C.Y.J., Au, K., Widz, M., & Jen, M. (2021). The Governance Marathon: Dynamic Durability in Entrepreneurial Families Amid Disruptions. Boston, MA: 2086 Society & the Family Firm Institute. https://digital.ffi.org/pdf/ffi_the_governance_marathon_report.pdf

3Tajfel, H. & Turner, J.C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

4Tajfel, H. & Turner, J.C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel &W. Austinn (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (2nd ed., pp. 2–24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall

5Cantor, N. & Mischel, W. (1979). Traits as prototypes: Effects on recognition memory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 38–44.

6Burke, P.J. (2001). Relationships among multiple identities. The Future of Identity Theory and Research, a Guide for a New Century Conference, Bloomington, Indiana.

7Burke, P.J. (2003). Relationships among multiple identities. In P.J. Burke, T.J. Owens, R.T. Serpe, P.A. Thoits (Eds.), Advances in identity theory and research (pp. 95–114). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

8Fiske, S. & Taylor, S. (1991). Social cognition (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

9Albert, S. and Whetten, D.A. (1985), Organizational identity, in Cummings, L.L. and Staw, B.M. (Eds), Research in Organizational Behavior, Vol. 7, JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, 263-295.

10Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2004). Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49(2), 173-208.

11Ravasi, D., & Schultz, M. (2006). Responding to organizational identity threats: Exploring the role of organizational culture. Academy of Management Journal, 49(3), 433-458.

12Hatch, M. J., & Schultz, M. (2002). The dynamics of organizational identity. Human Relations, 55(8), 1004.

13Taguiri, R., & Davis, J. A. (1992). On the goals of successful family companies. Family Business Review, 5, 43-62.

14Family business group identity often integrates Investor Identity, next to Owner Identity because these families would usually experience different dynamics when investing into expanding the families’ business portfolio and cannot stay “bonded” with every firm in the portfolio.

15Thomsen, S. & Pedersen, T. (2000). Ownership structure and economic performance in the largest European companies. Strategic Management Journal. 21(6), 689-705.

About the Contributor

Marta Widz, PhD, is a member of FFI, IFERA, and AOM and was co-chair of the 2020 FFI global conference program committee. A specialist in governance, sustainability, and family offices, she has worked with large, global, and multigenerational family businesses. She is currently working with family offices at the Wealth Management Institute in Singapore, acts as executive in residence at INSEAD, and is affiliated faculty at the Family Business Institute of the University of Vermont. She obtained her PhD at the Center for Family Business at the University of St. Gallen, Switzerland, and was a research fellow at the IMD Business School in Lausanne, Switzerland. She can be reached at martawidz@wmi.edu.sg.

Maria José Parada, FFI Fellow, Associate Professor, is director of the strategy and general management department at ESADE and academic co-director of the ESADE Global Business Family Initiative. She holds a PhD from Jönköping International Business School and a PhD from ESADE Business School. She teaches family business courses and strategy. She has been a visiting researcher of the INSEAD Global Leadership Centre in France and a visiting scholar in HEC Paris. She can be reached at mariajose.parada@esade.edu.

View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.