View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.

Continuing our quarterly series on the FFI conference theme, “Mean Time: Time, Timing, and Timelessness in Family Enterprise,” through the month of July we are pleased to feature issues related to presentations that will be made in London in October. Thank you to FFI Fellow Jeremy Cheng for this week’s issue, “Governing Legacy: Going beyond the Governance Marathon.”

During an enterprising family’s conversation with an advisor, the advisor asks, “What legacy do you want to leave behind?” The patriarch responds, “I want my children to remain united, nurture the family business, and avoid conflicts over wealth. We already have more than enough money for this generation and beyond.” In a separate interview, the eldest son makes a request: “I don’t want to inherit his wealth. Please exclude me from the plan.”

As advisors, we often encourage matriarchs and patriarchs to contemplate the meaning of legacy as they prepare for leadership and wealth transition. When considering how to safeguard their hard-earned legacy, we sometimes recommend establishing a family governance system. We view legacy management as a skill within the family, one that can be strengthened through the creation of governance structures such as family constitutions, family councils, and family offices. However, it is important to acknowledge that this legacy-governance linkage lacks both conceptual and empirical validation.

Let’s pause and explore the term “legacy.” Interestingly, finding an exact translation of this word in Chinese proves challenging. My academic colleagues from various parts of the world encounter the same issue. In the literature, legacy encompasses material aspects (such as wealth and property), social elements (such as the founder’s entrepreneurial values and their narratives of resilience), and biological connections (such as bloodlines). Through my research, I have also identified meaningful distinctions between family legacy, family business legacy, founder’s legacy, and entrepreneurial legacy. As advisors, we play a crucial role in helping families recognize these subtle differences and understand how various stakeholders interpret the concept.

From Legacy to Legacy

In the opening vignette, wealth is not the central issue. Rather, it’s how the two generations perceive legacy—the wealth, in this case—differently. While the patriarch never intended to wield wealth as a means of control, this perception is deeply ingrained in his eldest son’s mind, shaped by decades of interactions with the patriarch. Consequently, the son’s decision to relinquish his succession rights becomes a way to reclaim his autonomy.

The nuanced interpretation of legacy is illuminated by a robust process model of legacy co-construction, as discussed in a recent article by Professors Miruna Radu-Lefebvre, James Davis, and William Gartner in the Family Business Review.1 According to this model, both legacy “senders” and “receivers” co-create legacy through social interactions. Rather than being fixed, legacy remains fluid and subject to constant evolution. Advisors’ bias toward legacy “senders” can sometimes lead to the development of governance structures that preserve the legacy as it stands, overlooking the active role played by legacy “receivers” in co-creating a legacy that truly benefits them and enables them to live in the plan.2

These perceptual differences in legacy are salient across generations. Legacy is intertwined with future-oriented visions, or “anticipated futures.”3 Samuel Curtis Johnson III, the retired chairman of S. C. Johnson, aptly stated, “Each generation has the responsibility of bringing to the business their own vision for the future of the business.”4 This generational vision serves as a guide for legacy development, while also allowing space for the emergence of new visions. I once met an inspiring family entrepreneur in Bangkok who embraced the concept of “legacy-to-legacy,” emphasizing his stewardship and commitment to supporting the evolution of legacy across generations.

Governed Legacy and Governance Dynamic Durability

Legacy emerges through the interactions between “senders” and “receivers.” These interactions are not isolated; rather, they are governed processes that involve negotiated power and coordinated intentionality. The concept of “governed legacy” establishes an invisible boundary within which receivers decode and interpret the legacy transmitted by the senders. As the legacy evolves over time, the underlying governance system must also adapt.

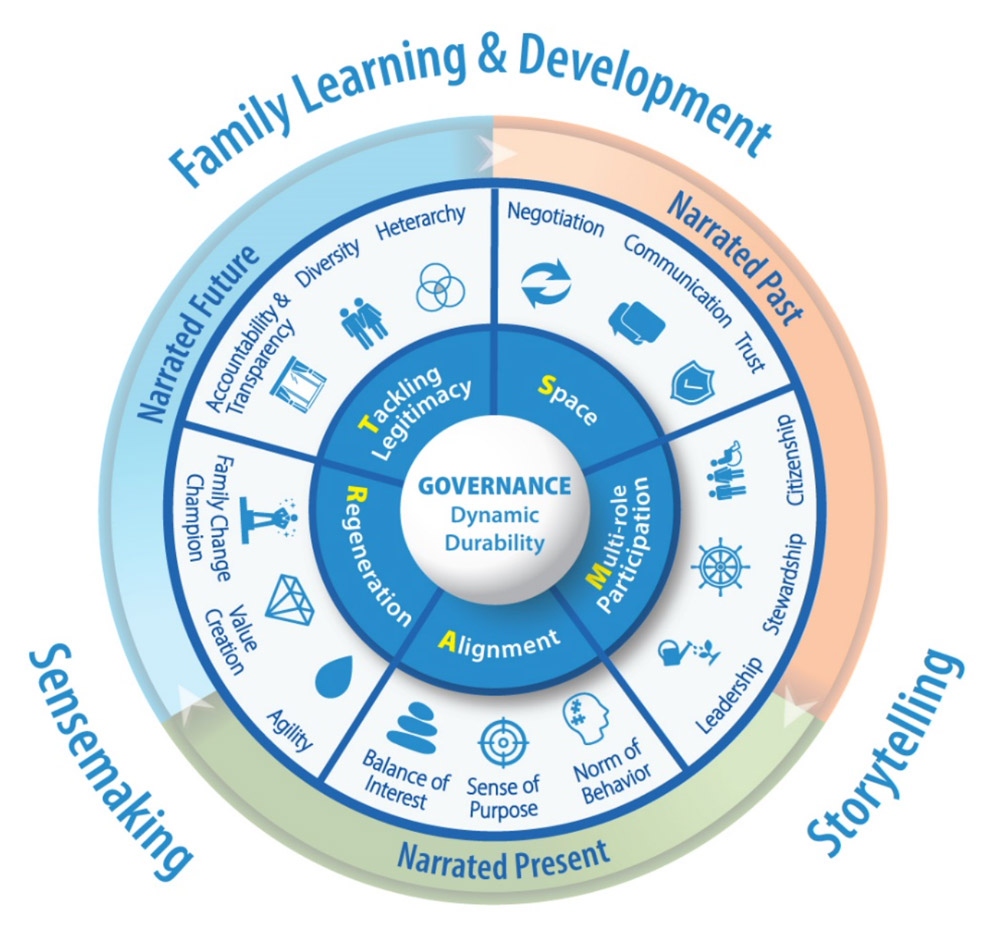

In a study titled The Governance Marathon,5 sponsored by the FFI 2086 Society, my co-authors and I introduced the concept of “governance dynamic durability.” This framework captures the enduring capacity of governance to navigate change and adaptation. The essence of dynamic durability lies in maintaining an open, living, organized, and adaptable governance system. Governance is a social practice with a technical component. The system remains alive and open due to the underlying governing practices, while the technical component defines essential organizational boundaries. Families, with their unique characteristics, activate and reactivate specific building blocks of dynamic durability. These include (i) Space; (ii) Multi-role participation; (iii) Alignment; (iv) Regeneration; and (v) Tackling Legitimacy. Together, these elements form what we refer to as the G-SMART model of dynamic durability (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The G-SMART Model of Dynamic Durability

As I consider how the G-SMART model can be applied to preserve and enhance legacy, the “technical component” converges with durable governance structures shaped by repeated governing practices. Over time, these structures become legitimized, creating boundaries for decision-making and routinizing processes to conserve cognitive resources. However, ongoing governing practices continually challenge and reshape these boundaries. When it comes to legacy interpretation, durable governance structures tend to transfer legacy as it is, emphasizing legacy continuity. In contrast, dynamic governing practices transform legacy, orienting it toward the future. Let’s explore each of the SMART building blocks in this context:

- Space: Forums that reinforce prior legacy interpretations can also be reopened for negotiation. Flexibility allows for evolving interpretations.

- Multi-role participation: Empowering rising-generation members as citizens of the governance system to interpret legacy from both stewardship and leadership perspectives. They honor the past while actively expanding the legacy for the future.

- Alignment: Collective efforts to sustain legacy involve agreed-upon purposes, behavioral norms, and a balance of interests. However, this alignment does not preclude the emergence of new visions or the need for realignments.

- Regeneration: Upholding the principle of value creation when deciding whether to reinterpret legacy. In positive cases, agility and family change champions play essential roles.

- Tackling legitimacy: Governed legacy involves negotiated power and coordinated intentionality. Rules of diversity, accountability, and transparency prescribed by the dominant power maintain the existing interpretation across family, business, and ownership structures. Yet, these rules can evolve, compelling the dominant power to reconsider legacy interpretation.

Ultimately, legacy interpretation results from the interplay between durable governance structures and dynamic governing practices. The balance between relying on structures versus practices varies among different families.

Temporal Orientation Toward Legacy

Advisors must understand the anticipated futures of their client families and where their legacy currently stands before determining how to deploy governance structures and governing practices. Building upon the G-SMART model, understanding how families temporally orient themselves toward legacy becomes relevant. Families exhibit varying emotional dispositions to the past, present, and future, which manifest in their narratives related to time. Examples below can assist advisors in assessing a family’s temporal orientation toward legacy.

- Temporal anchoring: Rather than reminiscing about time linearly, families often anchor their narratives around significant events. These events are deliberately chosen by the dominant power (the governor or the governance alliance) and strategically memorialized to establish legitimacy. Governance leaves temporal markers that shape the intended legacy. Sometimes, narratives related to taboo events are suppressed or selectively forgotten to favor the dominant power. Repeated temporal markers associated with the same lineage of dominant power may indicate a retrospective orientation toward legacy.

- Bracketing and periodization: Families interpret events not solely based on their actual duration but by bracketing and periodizing them. For instance, a founder’s long effort to establish the company might be condensed into a single developmental phase. In contrast, achievements of a rising-generation leader, even if much briefer in actual duration, may be categorized as separate phases of development, signaling a prospective orientation.

Strategizing Approaches to Governing Legacy

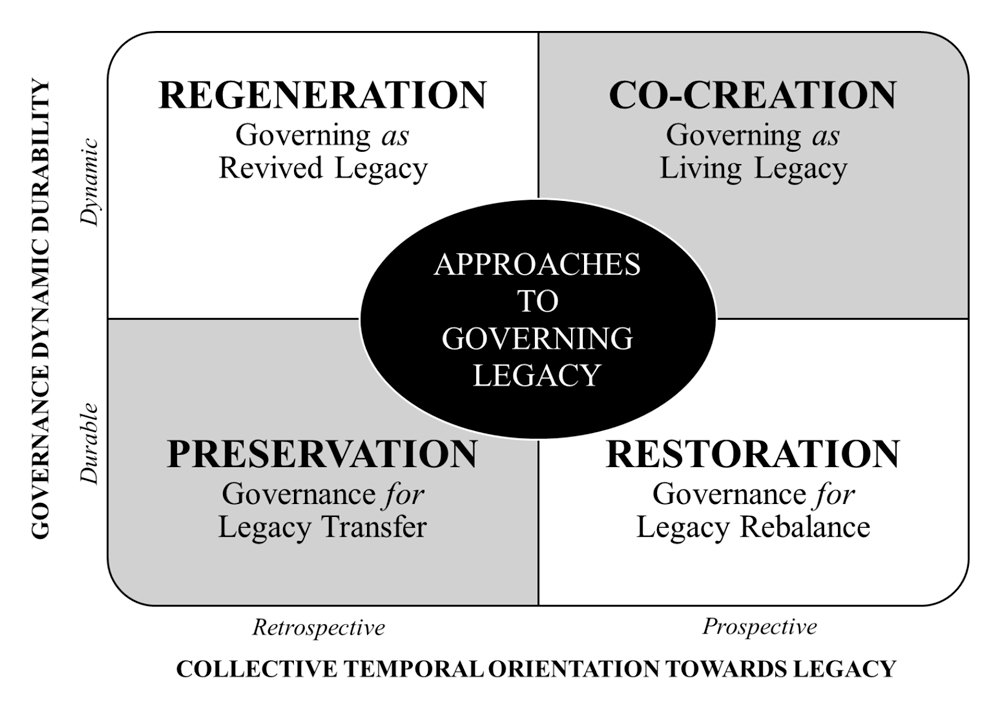

Understanding a family’s temporal orientation toward legacy is crucial for advisors. Once this orientation is clear, advisors can work with client families to develop an effective approach to governing their legacy. However, a misalignment between the family’s temporal orientation and their dynamic durability can lead to significant repercussions. Consider the example of “dead-hand control” within trusts—a common legal structure established by business founders to preserve family wealth as a legacy. When trusts are rigidly set and fail to accommodate the prospective orientation of beneficiaries who seek greater autonomy over family assets, trustbusters often step in. Unfortunately, this intervention can also unearth unwanted family conflicts.

In my upcoming London session, I will introduce a model that encompasses four distinct approaches to governing legacy, namely (i) Preservation, (ii) Restoration, (iii) Regeneration, and (iv) Co-creation (see Figure 2). Each approach caters to families in different life stages. Families will have to adjust their approach as their anticipated futures evolve across generations.

Figure 2. Approaches to Governing Legacy

Conclusion

Legacy provides a sense of order, bridging the past and the future. Legacy is not immutable; rather, it is co-constructed by both legacy senders and receivers. Each generation’s fresh vision reshapes the legacy and the narratives that underpin it. Whether families aim to preserve or transform their legacy, they need a corresponding approach—one that balances adherence to existing governance structures with the innovation of new governing practices. In this process, advisors work closely with client families. Together, they identify the family’s vision, assess the dynamic and durable aspects of their governance system, and strategize an approach that prepares them for generational transitions.

References

1 Radu-Lefebvre, Miruna, James H. Davis, and William B. Gartner. “Legacy in Family Business: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda.” Family Business Review 37, no. 1 (March 2024): 18-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944865231224506.

2 Allred, Stacy L., Mary K. Duke, and James E. Hughes, Jr. “Can Your Client’s Family Live in the Estate Plan You Create?” Trusts & Estates (September 2022). https://jehjf.org/can-your-clients-family-live-in-the-estate-plan-you-create/.

3 Barbera, Francesco, Isabell Stamm, and Rocki-Lee DeWitt. “The Development of an Entrepreneurial Legacy: Exploring the Role of Anticipated Futures in Transgenerational Entrepreneurship.” Family Business Review 31, no. 3 (September 2018): 352-378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486518780795.

4 Poza, Ernesto. Family Business, 3rd Edition. Independence, KY: South-Western Cengage Learning, 2010, 100.

5 Cheng, Jeremy, Kevin Au, Marta Widz, and Marshall Jen. The Governance Marathon: Dynamic Durability in Entrepreneurial Families amid Disruptions. Boston, MA: 2086 Society and Family Firm Institute, 2021-2022. https://digital.ffi.org/pdf/ffi_the_governance_marathon_report.pdf.

About the Contributor

Jeremy Cheng, PhD, FFI Fellow, is founder and consultant of GEN+ Family Business Advisory & Research and advises families-in-business, family offices, and other professional firms in Asia. Jeremy is also an adjunct assistant professor at CUHK Business School, with teaching and research focusing on governance, family office, and family advisory practices. An FFI board member, GEN faculty member, and FFI Fellow, Jeremy is founding chair of the FFI Asian Circle Virtual Study Group and recipient of the 2021 Barbara Hollander Award. He was a global survey/case committee member of the STEP Project Global Consortium. Jeremy can be contacted at jeremycheng@link.cuhk.edu.hk.

View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.