View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.

In this issue of FFI Practitioner, we are pleased to feature an article, “Judgment in Family Firms: What You Can Do to Improve Yours,” by the 2086 FFI Scholar-in-Residence, Sir Andrew Likierman. Likierman is the former dean of the London Business School and is currently Professor of Management Practice at LBS. In this article, he reviews key elements in making good judgments when consulting with a multi-general family enterprise, bringing his own experience as a family enterprise member to bear.

Professor Likierman will be working with FFI and its many colleagues and friends throughout the year to bring additional insights and commentary to the field. Thanks to the 2086 Society for its ongoing commitment to applied research.

At the FFI Global Conference in London in October, I explained why improving your judgment can be key to the quality of choices in family firms and those advising them. I came from the background of a family textile firm myself, so I well know what a difference the quality of judgment makes. We were into a new technology early, got the timing right to bring in outside capital, and forged an alliance with a powerful multinational when things got tough. There were also poor judgments, such as overconfidence leading to overexpansion.

I’m sure everyone has their own examples. The ones that come to mind are often where things go wrong, such as trust in someone who gave the wrong advice, costing a fortune in tax. Or as in the case of my own family firm, overconfidence in people or investments leading to unnecessary losses. Another example might be failing to pick up the signs that a member of the younger generation isn’t capable or motivated to take on responsibility. Then there is a single option being offered when other possibilities are available or a plan which assumes that the family will agree when, realistically, they won’t.

So, the stakes are high. For those who were not at the conference, here is a summary of how you can recognize judgment in yourself and in others and what you can do to improve your own.

Step 1

Let’s start with defining what judgment is—the combination of personal qualities with relevant knowledge and experience to take decisions and form opinions. Note that it’s not just about decisions—you form opinions about people and situations without making a decision.

Step 2

Understand that it’s a process. Judgment isn’t a mysterious quality that we have or don’t, one that we are born with or not. The question you have to ask yourself with a judgment to make is, “How do I stack the cards in my favor?”

Step 3

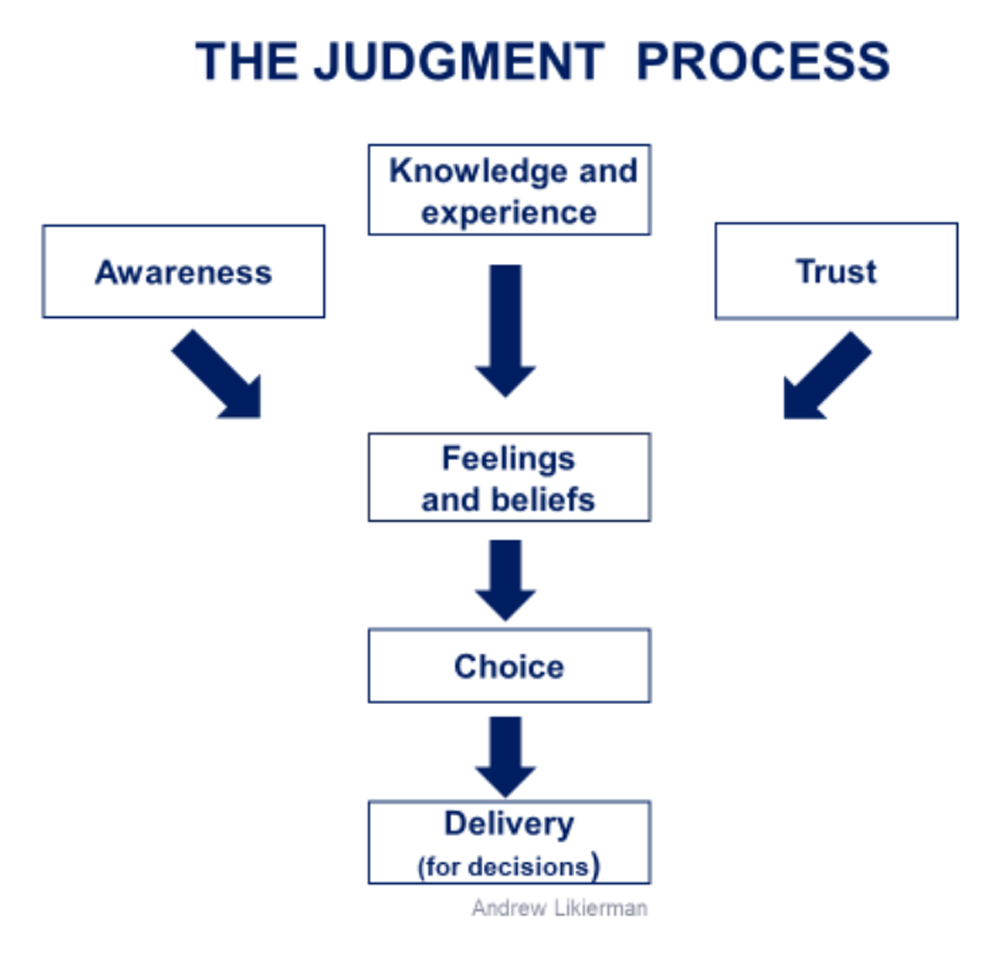

Apply the process to individual judgments, especially those where the stakes are high. This process has several elements, illustrated in the chart below:

- What you know that is relevant, including your relevant experience for this choice. An example would be how much knowledge and experience are relevant when advising a family firm on outsiders to help it on its next stage.

- Your awareness of what is happening, including the relationships and dynamics between family members, such as the role of influential spouses and the reality of whether siblings can get on with each other.

- Who and what you can trust, including both family members and those who advise them. Even those who want to help may be dominated by their own feelings, which get in the way of good advice.

- Your feelings and beliefs, such as on the role of family members in comparison with professional management. A proud or anxious parent may not be best placed to assess whether young Jacqueline or Jack would be good at managing that complex project.

- The way you make your choice, particularly on such key matters as succession, compensation, or dividends. In a big family gathering, will those who know that investment is desperately needed be prepared to speak up to persuade those only interested in bigger dividends or higher salaries?

- Your ability to deliver that choice. This might be about the reality of plans put forward for the governance of the business in light of opposition from influential family members (“Yes I know that we are a listed company, but without the family this business would be nothing.”).

You don’t have to apply the whole process each time, but applying any of these is better than not applying them—the more the better. Filling in gaps in knowledge or improving the way choices are made are worthwhile actions in their own right, regardless of how of the process is used. Nor need the process only be used in the sequence of the chart. Sometimes it is better to go back and look at what has already been assumed to be fine, as when too few choices are presented or when more facts need to be assembled.

Step 4

Be aware that there are many ways to improve your own judgment. This starts with finding what you are less good at and taking steps to remedy it—for example, recognizing what you don’t know and getting help from someone you can trust. It also means being aware of the quality of the judgment of those you work with. Finding colleagues with good judgment will improve the whole team.

What does this mean in practice? Examples include matching family capabilities to requirements; investment and dividend distribution policy; succession planning; the choice of advisors; the degree of formality in family arrangements; at what stage to bring in professional management; turning values into policy; when to bring in outside finance. It also applies to the way the firm operates. This might be as general as clarifying its culture or as precise as being transparent with outsiders about their chances of getting senior positions if they are not members of the family.

Managing risk comes into all elements of the process. It starts with being aware of what risks are involved, such as when coping with differing levels of uncertainty. It incorporates being explicit about the risk tolerance or appetite of individuals so that these can be taken into account when deciding between options. It is part of the way choices are made when alternative courses of action are offered. It is part of understanding, and taking steps to mitigate, execution risk.

Of course, judgment is not the only quality you need in yourself and others, but using it is a lot less painful than learning by making serious mistakes. You also need it yourself, and in those you work with, to improve the quality of management in general and leadership in particular. In summary, applying it gives you a better chance of making better choices—clearly vital where the stakes are high.

If you would like to know more about what actions to take, my new book will come out this month. An online course is also available. The sidebar gives details of both.

About the Contributor

Sir Andrew Likierman, FFI 2025 Scholar-in-Residence, was the Dean of London Business School from 2009–2017 and is currently Professor of Management Practice. His research, before working on managerial judgment, was in the fields of performance measurement and public finance. In his career as an executive, as well as running the London Business School, Andrew has worked for his own family’s textile firm. He has also started his own book business and for 10 years was Head of the UK Government Financial Management Service.

View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.