Lanie Jordan, co-chair of FFI Practitioner Editorial Committee interviews UMass’s Alan Robinson on corporate creativity and innovation.

“In organizations with effective idea systems, roughly 80 percent of overall performance improvement comes from front line ideas.”

Dr. Alan Robinson

Lanie Jordan (LJ): Alan, please share with our readers how you became interested in studying, researching, and assisting companies with corporate creativity and innovation?

Alan Robinson (AR): In 1985, I graduated with a PhD in industrial engineering at a time when efficiency experts were in high demand. Around this time, Japanese companies began landing higher quality products at lower prices within the United States. It became clear that something was different than anything I understood. I had an advantage in that my father was a professor at Tokyo University and my brother lived and worked in Japan. This access allowed me to live in the region and study 40 Japanese companies.

During this time I met my mentor, Shigeo Shingo of the Singho Prize and co-developer of the Toyota production system. Singho said, “Don’t pay as much attention to mathematics but focus on engaging all of your workers. Spend time developing a learning organization where all employees, top to bottom, are participating in continuous improvement and innovation.”

This lesson caused me to shift my focus from activities from working on one of the largest programs for the defense department to acknowledging that you can’t run most things from the center. Shingo taught me that you must engage people and get them involved in the process of innovation.

LJ: What are the typical missed opportunities you see with family firms in regards to innovation and how can we, as advisors, recognize and address these issues?

AR: I am watching a family business go out of business after three generations. This family has had a strong patriarch who led from the top, and you can’t run a company like that anymore. This particular company has outdated products, their production processes are outdated, and the workforce knows this.

In this case, there isn’t that humility for the leadership to acknowledge that it has 150 employees who know a lot of things that the leaders don’t know. Their employees interact with customers, vendors, and suppliers, giving them a wealth of ideas to move the company forward and the leadership needs to act on those ideas.

The biggest mistake in family firms is not having mechanisms for continuous improvement or innovation. I always begin with, “Tell me what systems, policies, and practices you have in place so that you know that tomorrow, next week, you will be slightly better than you are now.”

Companies need a department, a person responsible for improvement, and clearly written expectations in all employee performance appraisals that speak to expectations around innovation. The world is changing now faster than it ever has, so if a company doesn’t have these mechanisms for adaptation it becomes archaic very quickly. In his book Thank You for Being Late, Thomas Friedman clearly defines the forces that companies need to acknowledge and respond to consider — forces such as innovation and globalization.

LJ: What part does disruption play in innovation and corporate creativity?

AR: Less than you might think. Disruption innovation, as a technical term, is defined by Wikipedia as “an innovation that creates a new market and value network and eventually disrupts an existing market and value network, displacing established market leading firms, products, and alliances.”

Where family businesses often struggle isn’t in the disruption, but in not having systems and processes in place to change on multiple fronts.

LJ: You utilize The Idea Board as a best practice to help capture and develop great ideas. Please tell us more about the tool and how practitioners can utilize it to assist a family in becoming more innovative?

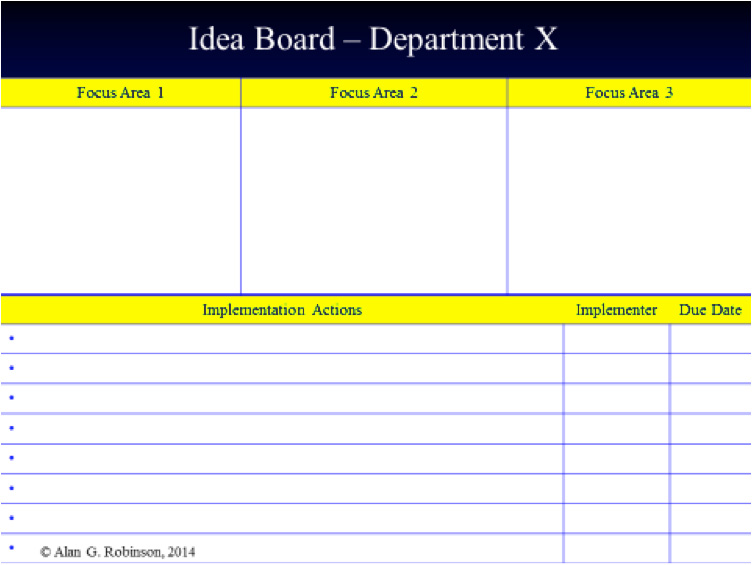

AR: The Idea Board is the most powerful and popular single tool for moving innovation forward and for capturing ideas and managing projects. Think of a graph provided on a large white board divided into two parts: focus areas and implementation actions. Management identifies the areas that the team should think about — each noted under the three focus areas. Frontline people begin brainstorming their ideas and identifying opportunities around each topic. They ask themselves, “How can we improve this area? “

The process becomes a weekly activity where employees begin collecting ideas and problems on post-it notes and throughout the week place these notes in the appropriate category on the whiteboard. The team then comes together for a meeting. Team members look at all the opportunities, ideas, and challenges listed on the white board and vote on which items the team should work on in that particular week. The team discusses the issue, asks the person who wrote it to tell the team more about the issue or idea, identifying the gap. Finally the team discusses and gathers ideas around the topic.

The team moves to the project management piece of the board at the bottom half and begins identifying “homework” or mini projects around the issue for the upcoming week. The goal is to have everyone on the team working for one to two hours on his or her assignment.

During the next weekly meeting, the team reports on its findings while implementing new ideas. The progression creates a structure to record issues as the team members see them, have everyone come together to discuss them, agree on what needs to be improved, and ensure that changes get implemented by the team.

Think of the Idea Board as a PDCA cycle (Plan, Do, Check, Act) on a white board. An Idea Board collects, prioritizes, and creates action as a team. Meetings aren’t complete until everyone has her or her assignment. The following week the team comes together to share findings, discuss, and adopt changes. This exercise, performed as a regular activity, creates continuous improvement making this process a virtuous cycle, not a vicious cycle.

LJ: What pitfalls should we, as advisors, avoid as we assist families in becoming more innovative?

AR: I believe learning opens doors and I believe in becoming a lifelong learner. I recommend that advisors educate themselves on continuous improvement, innovation, and creativity.

Secondly, educating the leadership team before beginning any new process with employees. Leadership must spend time and embrace this management shift and creation of a new culture.

With my clients, I recommend that leadership spends a day or two with me before implementation. Shifting to an idea-driven organization requires management acceptance and understanding of the time it takes for employees to work on projects and ideas.

We then assess this time away from traditional production and how that impacts the bottom line, customer retention, and employee satisfaction. This ROI helps build the case for spending time on activities that move companies forward — creating a learning organization. I’ve never seen a learning organization that isn’t highly profitable.

LJ: What parting advice do you have for advisors around the topic of corporate creativity and innovation with our family business clients?

AR: Become a master of it yourself. Below are a few resources I typically recommend for those who want to delve deeper into the subject of innovation and corporate creativity.

One way to make the case in leadership is to talk to the rank and file. I typically spend time with the front line individuals, Tom Peters spoke to my students, and one student asked, “What makes a great advisor to a company?” Tom responded, “The best consultants spend time in the mailroom, not in the boardroom.” Meaning that leadership is typically capable, smart individuals who know what they know. Employees see day to day opportunities with customers, vendors, and suppliers and have ideas that management typically doesn’t see.

Suggested Resources

Corporate Creativity, Alan Robinson and Sam Stern, Berrett-Koehler

Ideas Are Free, Alan Robinson and Dean Schroeder, Berrett-Koehler

It’s Your Ship, Michael Abrashoff, Warner Books

The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, C.K. Pralahad, Wharton School Publishing

The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton Christensen, Harper Business

The Ten Faces of Innovation, Tom Kelly and Jonathan Littman, Doubleday Currency

About the contributor

Alan G. Robinson specializes in managing creativity, ideas and innovation, and is the co-author of seven books, which have been translated into more than twenty-five languages. Dr. Robinson is a professor at the Isenberg School of Management at the University of Massachusetts and has advised more than three hundred organizations in thirty countries on how to improve their performance. He received his PhD in applied mathematics from the Johns Hopkins University and a BA and MA in mathematics from the University of Cambridge. He can be reached at agr@isenberg.umass.edu.

Alan G. Robinson specializes in managing creativity, ideas and innovation, and is the co-author of seven books, which have been translated into more than twenty-five languages. Dr. Robinson is a professor at the Isenberg School of Management at the University of Massachusetts and has advised more than three hundred organizations in thirty countries on how to improve their performance. He received his PhD in applied mathematics from the Johns Hopkins University and a BA and MA in mathematics from the University of Cambridge. He can be reached at agr@isenberg.umass.edu.