View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.

Thanks to Michael Madera for this article discussing three wise moves to help your family enterprise clients understand and respond to external crises.

Crises in public health, business, and socio-political arenas present significant challenges to businesses of all kinds. As this article is written, in June 2020, we are experiencing a perfect storm moment, coping with three simultaneous upheavals and one slowly unfolding crisis:

- the global COVID-19 pandemic;

- extraordinary business conditions, including staggering reductions in consumer demand during lockdowns, and double-digit unemployment;

- in the US and elsewhere, protests for racial justice and controversies over the role of police and the military to maintain law and order; and

- all this taking place against the backdrop of climate change, which is increasing the volatility and extremes of weather patterns globally.

Families in business are challenged to develop responses and strategies to survive and cope with these conditions, especially in the short term. These moments also provide unprecedented opportunities to consider incremental or more substantive change.

In times like these, as a psychologist, I feel the need to first emphasize the importance of starting with compassion and understanding, for yourself and others, as you decide how to respond. Crises are deeply stressful, people respond in different ways, and attention and additional support can be very beneficial and appreciated.

As you turn to the questions of how to understand and respond to the crises and their impacts on your clients’ business and family, I hope this article describing the following three question reflective model is helpful:

- What? – to understand what is happening and where attention is most needed, build a comprehensive dashboard model to triage situations and assess risk in business and family arenas.

- So What? – to help understand the significance and choose the most appropriate problem-solving process for each situation, consult a model drawn from Complexity Theory.

- Now What? – to select among options for how to respond, use a Levels of Change framework, while comparing these to your personal and/or organizational disposition and preferences.

1. What? – Assessing and qualifying risk.

During a time of crisis, leaders are well served to make a comprehensive inventory of areas of concern across multiple domains. This inventory can help uncover pockets of strength and opportunity as well as risks and concerns.

One way to build this inventory is to use a dashboard tool, which lists all relevant areas of concern, and captures information to assess risk using a Green-Yellow-Red categorization.

- Red: Functioning is highly impaired or stopped, emergency-level concerns that need immediate and significant attention and support.

- Yellow: Functioning is impaired or diminished, urgent or ongoing concerns that are likely to be resolved with additional attention and/or resources.

- Green: Functioning well and goals achieved, managing stressors, fully executed plans in place, little or no need for attention.

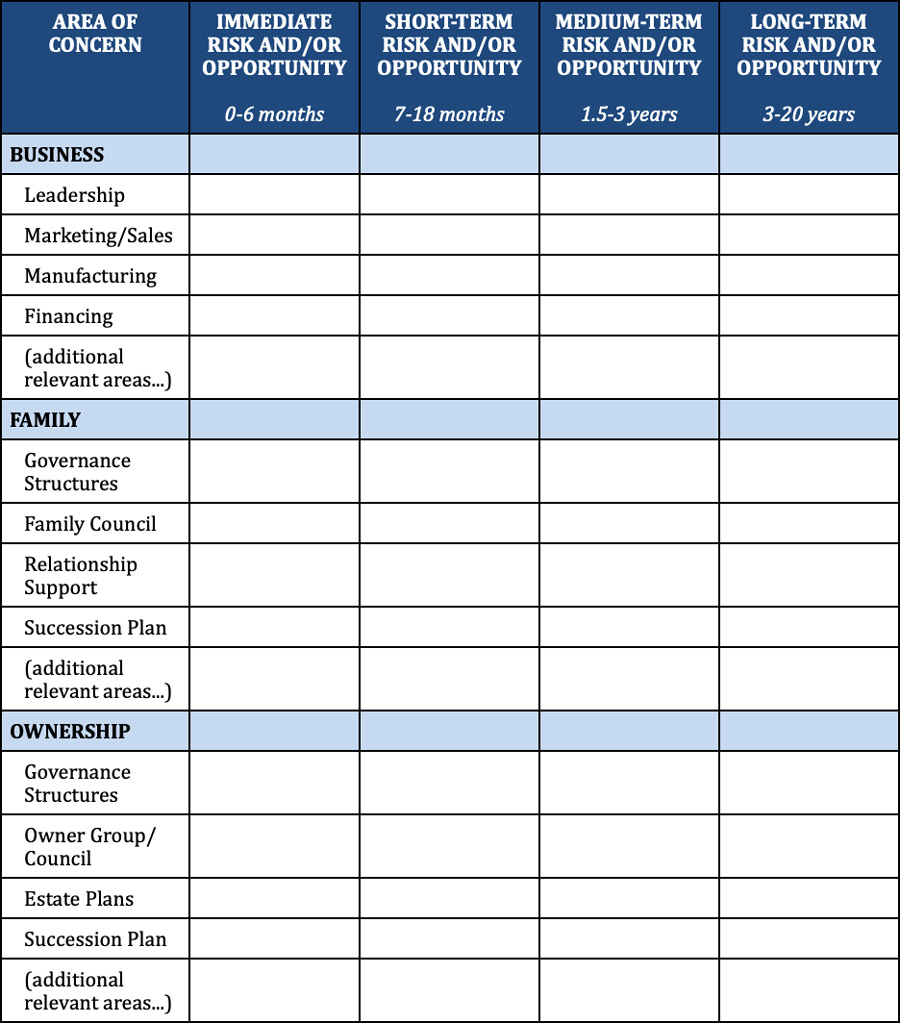

In this example, analysis is organized using the categories of the Three- Circle Model, and the long-term timeframe is provided given the multi-generational nature of families in business.

The results can provide a bird’s eye view to inform action and strategic planning. This approach also helps leaders ask themselves and their stakeholders about immediate areas of focus due to the crises, and if repeatedly updated, invites a review of risks and opportunities over time.

Family enterprise leaders can ask questions such as:

- Given the disruptions and shifts you are seeing in your area of concern, what changes or opportunities becomes more possible or achievable in each time frame?

- In your area, where do you see an opportunity to address goals that have not yet been achieved or are emerging due to recent shifts?

- How might you connect with and support other areas of concern in more effective or new ways?

As an example, a family enterprise client in Real Estate Development might use this analysis to connect a plan in the Business to update large credit facilities with initiatives for Ownership structure and estate planning and would be able to coordinate these for optimum valuation and favorable tax impact.

2. So What? – Choosing the best-fit problem-solving approach for each challenge

Once a problem or opportunity has been identified, success will be much more likely if the approach is appropriate to the level of complexity involved. Just as you wouldn’t bring a bucket of water to a forest fire, or a hammer to repair a computer, you wouldn’t want your clients to address a business or organizational challenge with an inadequate or inappropriate approach.

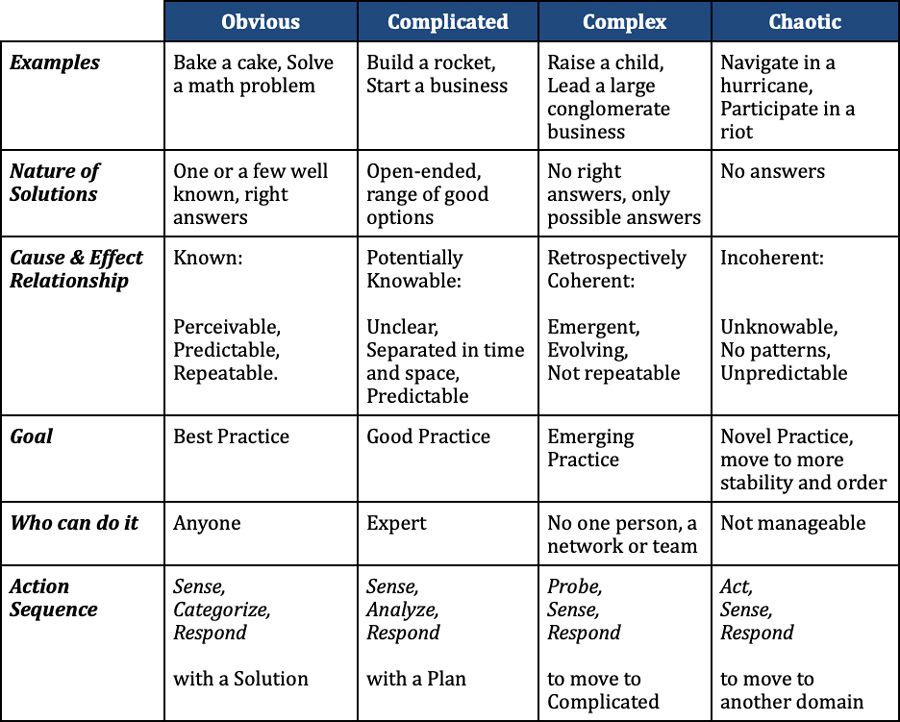

The Cynefin Framework,1 (pronounced ku-néh-vin), developed in 1999 by Welsh scholar Dan Snowden, offers a way to evaluate situations in terms of predictability of outcomes using four categories: Obvious, Complicated, Complex, and Chaotic. It also provides guidance to choose the most appropriate methods to analyze and address them.

The table below provides an overview and suggestions to help you apply the model to many challenges your clients might be facing:

Author’s Summary of Cynefin® Framework

In times of crisis and rapid change, many situations fall into the Complex or ‘wicked problem’ category. These are multi-determined, non-repeatable situations that defy simple solutions or expert judgment, such as the movement of financial markets and the behavior of family members under stress in a large family system. The Cynefin distinctions can help us to see the risk of underestimating the challenges in a crisis, and avoid the tendency to treat unknowable Complex problems as if they could be solved using a pre-existing plan or formula. The best approach in these situations is to conduct many small, low risk experiments and analyze the results to understand the emergent, evolving nature of the situation. Once enough data and experience has been gathered, the goal is to then develop flexible approaches or ‘rules of thumb’, and eventually apply expert analysis and address the situation as a Complicated problem.

3. Now What? – Deciding how to take action

Once the problem areas and their level of complexity are identified and understood, it is crucial to develop a vision and plan to move forward. Crises, however painful, also serve to loosen constraints and expand the range of options usually considered too risky or impossible to accomplish. In the COVID-19 crisis in the US, for example, we have seen $2 trillion USD stimulus payments to individuals in the first few months, plus hundreds of billions more in financial aid distributed to businesses (compared to $1.5 trillion for the entire 2008 financial crisis). Despite the dynamics of crises, our personal preferences towards change can limit the options we consider, and we risk missing opportunities to take, facilitate or recommend action for far-reaching changes that could have great benefits.

Research has confirmed2 that people have varying comfort and interest in change, and in 1997, Rolf Smith proposed a model of 7 Levels of Change which can be grouped into three categories:

Getting Things Right:

1) Effectiveness: Doing the right things

2) Efficiency: Doing things right

3) Improving: Doing things better

Doing Other Things:

4) Cutting: Doing away with things

5) Copying: Doing what others are doing

Doing Different Things:

6) Different: Doing things no one else is doing

7) Impossible: Doing things that can’t be done

Crises often push us out of the domain of the steady and stable ‘Getting Things Right’ category and invites us to do ‘Other or Different Things’ to meet shifting and emergent challenges.

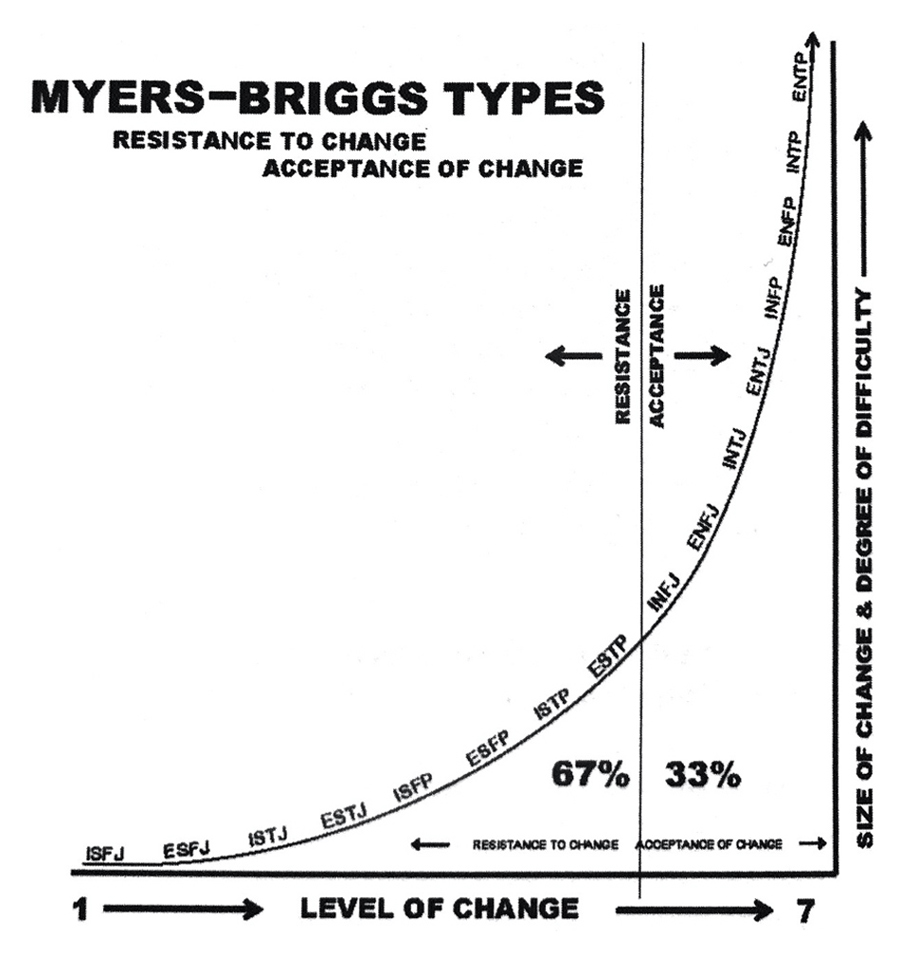

When we are told to isolate ourselves at home, when our client’s business comes to a halt due to lack of customer demand, when protests call for fundamental social change, we are well served to consider a wide range of responses. The difficult thing is that research on innovation and personality type has found that 67% of people are resistant to changes above Level 3! Families and organizations also display persistent cultural patterns, and many strive for stability, consistency and predictability. The graph below shows the 16 Myers-Briggs Personality Types along a spectrum of resistance and acceptance and promotion of change.

Source: The 7 Levels of Change, Rolf Smith, 1999

So, when considering how to respond to crises, it is important get clear about your own and your clients’ preferences and biases towards change and consider ways to increase the range of options.

Strategies might include the following:

- Assure that you and your client family or team solicit and consider options at each level of change;

- Strive to be open to reforming or re-imagining an area or function to meet the demands of the crises as well as the many and profound changes that have occurred in society and business over the recent decades; and

- Plan to provide support and guidance to the many people and organizational units where the experience of change is a very real and significant challenge and stressor.

Hopefully, the approaches in this article can help you and your clients in times of crisis to proceed wisely and prosperously, by identifying business, family, and ownership areas that need attention; understanding the nature and complexity of problems; and considering a full range of options for responding to and/or creating change.

References

1 Snowden, D. and Boone, M. (2007). ‘A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making,’ Harvard Business Review, November 2007. https://hbr.org/2007/11/a-leaders-framework-for-decision-making

2 https://kaicentre.com/kai-and-j-p-dimension-of-the-mbti/

About the Contributors

Michael Madera, Psy.D. is an FFI Fellow and the President of Madera Partners, a boutique consulting firm near Boston. He is an advisor, executive coach, and organizational consultant to families in business with more than 20 years’ experience and has helped many families achieve their goals and improve their working relationships. He did his psychology training at Harvard University, and has served as Master Coach Supervisor and Faculty at William James College. Michael served as a member of the FFI GEN faculty from 2012-2017. He can be reached at michael.madera@maderapartners.com.

View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.