View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.

Continuing our quarterly series on the 2024 FFI conference theme of “Mean Time: Time, Timing, and Timelessness in Family Enterprise,” we are pleased to present a podcast interview with Krishna Thapa, a “warrior monk.” Born in Nepal, a Gurkha, and a member of the British SAS, he is now a mountain specialist whose mission and lived commitment is “enlightenment through adversity.” This podcast is brought to you by the FFI 2086 Society and its 2024 grant recipient, the Nomadic School of Business. To join the August 6 webinar with Krishna and FFI Fellow Paul Milne, go here to register.

Podcast Transcript

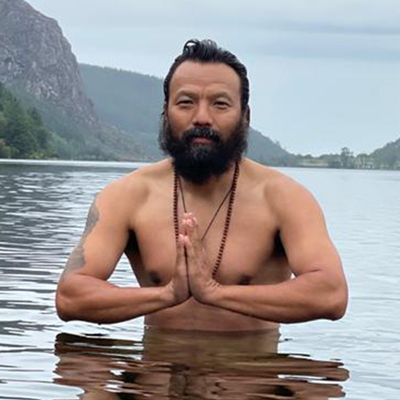

Jordan Rich (JR): Welcome to the FFI Practitioner podcast, featuring Krishna Thapa, presented by the FFI 2086 Society and the Nomadic School of Business. Krishna is a “warrior monk” whose life is a testament to service and resilience. Raised in the Nepal Himalaya beneath Annapurna, his journey began by joining the British Gurkha at 19. A bit later he entered the British SAS. With 26 years of frontline service, Thapa’s roles included mountain specialist and mental health advocate. He holds the Guinness World Record for leading the largest group to ever summit Mount Everest. Now focused on guiding and training extraordinary individuals, his path inspires courage, control, and connection. We welcome you Krishna, and to begin, I invite you to share with us a bit of your backstory.

Krishna Thapa (KT): Thank you very much. For me this is a great honor from the “Land of God,” Nepal. In Nepal, in my tribe, the eldest son before he is even born, has dedicated his life to the worship of nature. So, before I even realized it, at age three to four, I had to start praying for nature. Our tribe’s upbringing is close with nature, our ritual and culture is based on that. And being the eldest son in my family, I had no choice—that’s actually built within the culture and society. And at the same time having said that, we lost my grandfather in the Second World War, with the British and Indian Army, and my parents had a dream for me to be a Gurkha, a British Gurkha, before I was born. The culture, over the past 100 years, has built up with the bloodline always with the warrior, [to] always connect with protecting ourselves, who we are and how can we still be at peace, [maintaining it] within us.

JR: That is a very noble cause to be a soldier and to be so dedicated. Now at nineteen you became a Gurkha, which is in the Indian culture, the soldier. And then not much later, you joined what’s known as the SAS with some of the finest trained warriors in the world. What prompted you to do that and was that a difficult transition, to go into that?

KT: In our life, in every situation we accept—accepting is defeating our own ego within us. After serving for about five years with the Gurkhas, one day my British commander called me into his office and said we’re going to send the Gurkhas for trial, to see how we do on the SAS. Of course, everyone had heard of the special forces and who they are, but I never realized I could be selected to join from the Gurkhas.

JR: You are the first, is that right?

KT: I was one of the first. There were few other Gurkhas from other regiments. We call our regiment Royal Gurkha Rifles [RGRs], I was one of the first. Two of us were the first to pass from the RGRs.

JR: Served over two decades on some very dangerous missions. Two skill sets that you possess: one is the expertise when it comes to mountaineering, and we’ll talk about that, and then you were also a mental health advocate and aide. Talk a little bit about both skill sets that have served you and the people you serve with so well.

KT: Thank you. I don’t call myself an expert mountaineer, because I was trained to fight on the mountain. I was trained for that. I was a fighter and warrior—how to save lives, save comrades and families, and the country that holds my family’s values. So I was trained for the mountains, but eventually, I think by [learning to survive in the mountains], that makes us who we are, and now, I end up climbing a few mountains I guess.

JR: Well, it’s interesting when you come from Nepal and you talk about mountains, there’s one mountain in particular that everyone is concerned with and interested in, and that’s Mount Everest. Before we go any further, you’ve had some experiences on Mount Everest. How arduous has it been, and what advice would you have for anyone thinking about doing it?

KT: There is a saying in Nepal: we worship the mountain. Treat it as a god or treat it as something beyond ourselves. By accepting that as our god, or whatever belief we have, then we can only go as we are and come back.

JR: Sort of a respect and an admiration in awe of this amazing structure that exists on Earth, and then working in a sense with it instead of against it. It sounds to me that that would be a good formula for success.

KT: Absolutely. By offering our service, our help, we shall always transcend our limitations, physical, mental, and emotional. Also from the mountains, I learned we all are climbing mountains in different ways. I can see and learn from looking at the mountain that our existence is very minimal in this universe. By accepting that, we can learn so much in our life.

JR: Krishna, you have spent a lot of your life in military service. Now you’re also spending a lot of your life trying to counsel people in the ways of peace. You call yourself the “warrior monk,” I love that. Let’s talk a little bit about how you in your own life have redefined wealth. Let’s start with that. What is it that matters to you, and all the experiences you’ve had? That wisdom is something that we in the West, I believe, can learn a lot from.

KT: I think that’s a very great question, thank you. I think for me, wealth is when we are at peace within ourselves.

JR: And for those who have been not at peace—and all of us have had troubles and trauma—when you find peace, you realize it’s the greatest gift you can give yourself, right?

KT: Yes absolutely. The peace—actually, all the conflict, all the war, in all the negative and positive, actually exists within us. One of the examples is whenever we pull the trigger on the rifles—a lot of people are thinking you have to clear the target or destination or the mission. But actually, the clear and concise focus only comes when we hold our breath, and the trigger has to pull back. The mechanism of the weapon has to draw back, so that you can focus within yourself and align with the mission. That is how we shall achieve our mission. The more we are at peace rather than reactive, that’s when we can start realizing life.

JR: And this doesn’t have to necessarily occur at the top of Everest or in a battlefield. This occurs every day, with our family, with our friends, with strangers we meet on the street, with business acquaintances, doesn’t it?

KT: Absolutely. Every moment and every breath, every heartbeat. If you have that power of focus, then everything we focus on becomes very clear.

JR: Your training in SAS is probably very similar to US Navy SEAL training here in the US. One of the things that I want to talk to you about is resiliency. When you build your body as you have, with physical activity, exercise, and regimen, that strengthens your mind, that strengthens your spirit, does it not?

KT: Absolutely. I think the core of good teamwork, good understanding, and trust within the team—and not only the team outside but our own team within us—how are our hearts, how are our lungs, and how are our feelings in teamwork within us? I think those are the fundamentals for us to be successful, whatever the outside circumstances are.

JR: Let’s talk a bit further about resiliency, about being able to bounce back when darkness hits. You’ve a no doubt seen comrades fall and seen people suffer in various parts of the world. How do you balance that with the light, with the good in your life and that you try to preach and profess to others?

KT: Truly, my profound understanding in my life is a lot of death. One of the things I realized, in the western world we never talk about death. In Nepal, for the men, when we are dealing with death, and for the women when they’re having a child are the most profound and challenging jobs they ever do during their life, because they are so close to understanding the death on their own.

JR: That’s very profound. You think about birth and death, those are the most jarring moments in any person’s existence, and yet we in the west want to ignore and not believe that it’s we’re going to happen to us.

KT: Absolutely. I think one of my realizations, after seeing a lot of death of my own friends in combat, also a lot of death in the mountains, and dealing with that death, is realizing once I looked in more profound way at death, I realized more about life. Then that allowed me to connect who I am now with my past as a child from Nepal and helped me to deepen my ritual practice.

JR: Adversity, which we’re all facing in various stages, if you try to duck around it and avoid it, and go under or just not deal with it, it’s going to deal with you. So, you’re preaching to a lot of people around the world the idea that there is enlightenment through adversity. Why don’t we just chat a little bit more about that, and then we’ll talk legacy.

KT: Absolutely. Every situation we face, outside or within us, it’s a constant conflict. Every conflict either we become wiser, or we become wounded. The choice is within us, in our own hand. The only way to do good, feel good, and pray and offer, is to focus on what we call positive psychology. We are not ignoring the negative fact, which is happening anyway, but by focusing our mind and our breath within us on the positive thing, that will come through understanding who we are and adversity. Changing our posture each time we face the challenge, both emotionally and psychologically, and that will eventually pass through an understanding closer to the peace of who we are and help us through adversity and understanding life.

JR: There isn’t really a lot of difference in philosophy between the East and the traditional religions of the West. When you come right down to it, the golden rule, “Treat people the way you would like to be treated,” and by all means, listen to the other side. Let’s talk about legacy. That’s one of the things you’re going to be focusing on in your 2086 Society seminar. I think about that a lot, because I want to know that what I’m doing makes a difference today and might just make a difference in the future. What what’s your take on how to develop a good feeling about legacy, and what it really means to leave one behind?

KT: I think legacy is so important for us as humans. One example was when I was leading a fourteen-man team in climbing K2, and the only reason I succeeded was because of my legacy, working with my SAS comrades and commander. Because there comes the time when your body’s giving up, your mind is giving up, and you have everything you work for is giving up. Yet again, you always have a clear vision and mission: the legacy you’re going to leave, which is beyond your life and death.

JR: We don’t realize how one action might affect one person or thousands of people.

KT: Absolutely. And it’s so important because if we live in the world of sensation—sensation is always related to pleasure, and if we live in the world [seeking pleasure], then there is no legacy. There is only reaction. But if you go live in what we call “chitta,” the word in Sanskrit which, in indirect translation is “soul,” and if you do something with your soul, it is beyond your life and death. [It] is scientifically proven [that] generational trauma can be passed through our parents and ancestors. As a human, we should always focus on how we can leave a good legacy to our next generation, which directly connects with our ancestors, our parents, and our grandparents.

JR: One would say you’ve led and continue to lead a rather exciting, adventurous life. What is in your future? What is it that you’d like to do that you haven’t done yet?

KT: One thing I’m working on constantly is exploring my own life and how can I leave the legacy of a good human being. On that note, I’m doing a world record event in June in support of children’s mental health in the UK. So that’s going to be one of the world record events I’m doing. It’s called the South North Adventures. I’m working with the two of my closest friends, one is Professor Kevin Dutton, who is a psychologist at Oxford and Cambridge University in the UK, and the other one is the World Championship rower Stephen Feeney. The three of us are doing the world record event South North Adventures, from the south of the UK to the north of the UK, and we’re going to raise the money for children’s mental health in the UK.

JR: You are a soldier of a different kind now, aren’t you? You’re a soldier for hope and peace. The world is a much smaller place—you’re speaking to me from your home, I’m speaking to you from the United States, we’re looking at each other, we’re seeing each other, your intense desire to be real is something that I can feel. I love that and I feel the same way. I want to be the real guy, talking to another human being. I can’t thank you enough for your time and your attention, not just to yourself but to all of us, so thank you.

KT: My pleasure and honor to share some of my lessons learned, and very much wishing all the best, all the life as well.

JR: Thank you to Krishna Thapa. His website is krishthapa.com. The next four issues of FFI Practitioner will feature articles by 2024 conference presenters, exploring the conference theme of “Mean Time: Time, Timing, and Timelessness in the Family Enterprise.” If you’re interested in participating in the August 6, ninety-minute online seminar with Krishna and FFI Fellow Paul Milne, please go to ffi.org to register. Learn more about this and other podcasts at ffipractitioner.org. This is Jordan Rich. Thank you so much for listening.

The start date of the South-North Adventure has been postponed.

About the Contributors

“Warrior monk” Krishna Thapa’s life is a testament to service and resilience. Raised in the Nepal Himalaya beneath Annapurna, his journey began by joining the British Gurkha at 19, later becoming the first to pass selection from RGR and enter the British SAS. With 26 years of front-line service in Afghanistan and Iraq, Thapa’s roles included mountain specialist and mental health advocate. Now focused on guiding and training extraordinary individuals, his path inspires courage, control, and connection.

Interviewer: Jordan Rich is celebrating a quarter century at one of America’s top legacy radio stations, interviewing thousands of celebrities, authors, actors and interesting personalities throughout his career. Jordan is co-owner of Chart Productions Inc, and also teaches voice-over acting. His main focus these days is in podcast creation and production, featuring conversations with the world’s most creative people.

View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.