View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.

In this week’s FFI Practitioner, FFI Fellow and 2022 recipient of the FFI Interdisciplinary Award, Jack Wofford shares insights he’s developed over nearly 30 years as a mediator working with family enterprises. In his article, he provides principles of negotiation and joint problem-solving as well as family enterprise examples.

Helping families achieve consensus out of protracted conflict is never easy. As a mediator and facilitator of family enterprise disputes for nearly 30 years, I share some insights from principles of negotiation and joint problem-solving that can be useful for a wide range of consultants and advisors.

A. The “Why?” Question: Separating “interests” from “positions”

Since 1981, the bible of modern negotiations has been Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In, by Roger Fisher and William Ury. A key insight of that book is for people in conflict to separate their “positions” from underlying concerns, hopes, and fears – that is, in the broadest sense, their “interests.”1 If people are locked into opposing “positions,” they tend to think that battle or compromise are the only ways out. If, however, they share their “interests” – those deeper concerns and personal priorities – there is opportunity to create an outcome that works for everyone.

Larry King excelled at pulling information from his interviewees. His strategy for interviews was to be honest about what he did not know, and his open curiosity would ease his guests into more relaxed conversation.2

In negotiations, King’s approach translates into the question, “Why?” To find out more about underlying thoughts and feelings, we ask, “Can you tell me more about that?” “Why is this important to you?” “You feel very strongly about this. What might be behind this?”

In a supportive and non-judgmental way, all family enterprise advisors can use friendly but probing questions to get at deeper issues.

B. Focus on the Problem

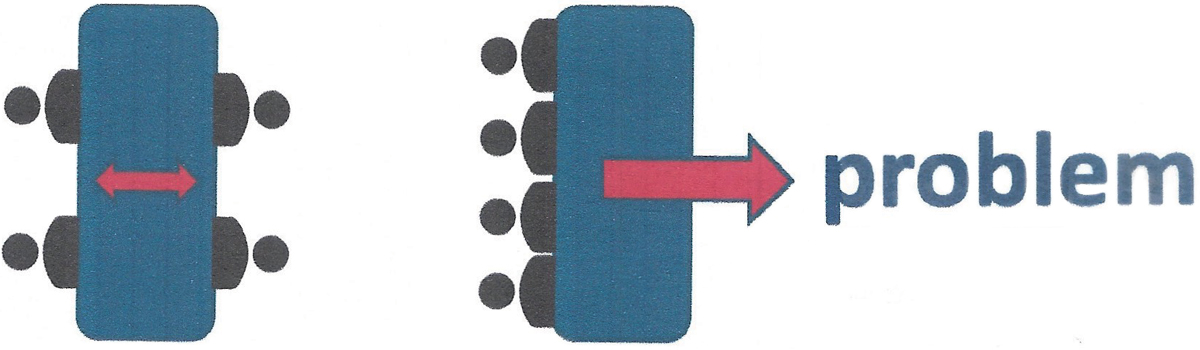

Another principle in Getting to Yes is to focus on the problem, not the people. While this is oversimplified, since often bad relationships among the people are a big part of the problem, it is nevertheless a useful formulation. One vivid way to convey the concept is to draw two tables – one with people on both sides facing each other, and the second with people on the same side facing the problem. I use this graphic frequently with families. It conveys not only the importance of understanding the problem, but the challenge to the family to think of themselves on the same side of the table. It serves as a reminder of how much they share.

C. Developing Order out of Chaos: “TRIANGLE OF INTERESTS”

Simple “interest-based negotiation” often doesn’t result in an agreement because “interests” are not thoroughly explored. In a family enterprise, the range of “interests” is so broad and expressed by family members in such a vivid, chaotic array that the advisor may worry about diving into chaos – from income disparity to feeling key data was withheld, from individual professional goals to liquidity needs, from interpersonal friction to differences over the future of the enterprise, from sibling rivalry to gender bias, from governance issues to questions of trust, respect, and fairness.

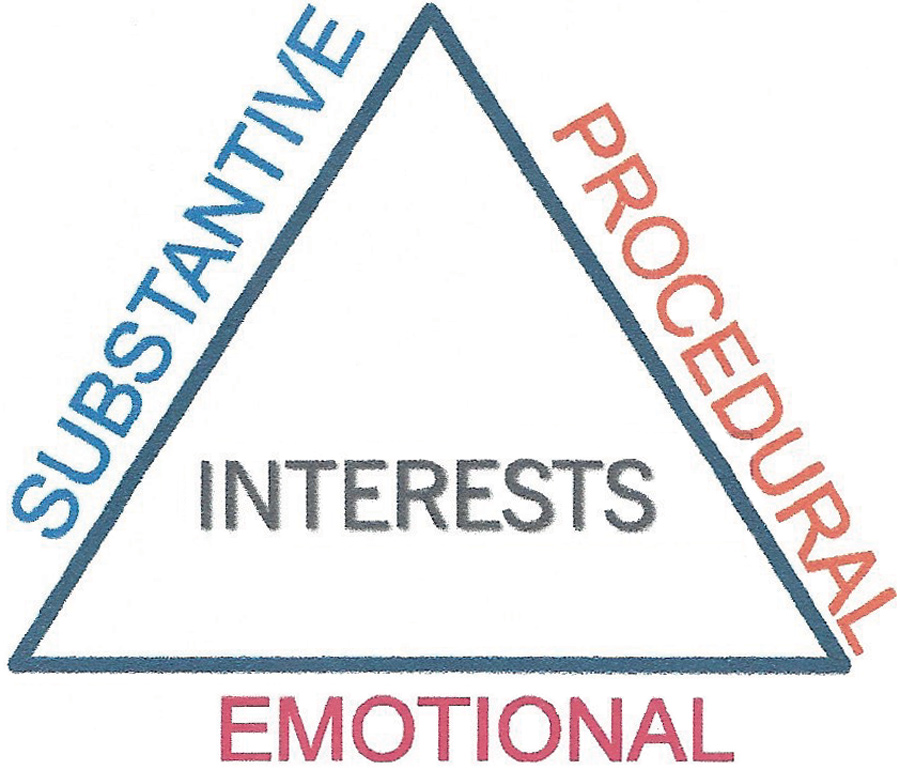

A useful conceptual framework is a simple triangle. One slope pointing toward the apex is labeled “Substantive,” the other upward slope is labeled Procedural, and at the base, the third – and often most important – side is labeled “Emotional.” These three organizing concepts appear in virtually every family enterprise conflict, often in raw form. I call it the “Triangle of Interests.”

The “interests” just expressed seem mushed together, but applying the Triangle of Interests can help pull them apart. Substantive Interest: Type of new counter. Procedural Interests: Effective consultation and communication. Emotional Interests: Sibling rivalry and feeling of victimhood.

This simple framework provides an opportunity to discuss each side of the triangle in a structured way, enabling the family to begin to grasp the complexities – but with some semblance of order rather than chaos. The Triangle is one way for the family to begin to untangle elements of conflict and deal with the pieces separately – and then put them back together.

D. Find Creativity in the Family Itself

One of the most satisfying aspects of working with families is to tap into their creativity to shape their own future. As facilitator, mediator, or consultant, I’m not hired to write a report and make recommendations. Rather, I make it clear that the family members themselves need to work at understanding their issues, creating options to deal with them – aided, of course, by insights from my experience – and crafting a solution that integrates as many conflicting interests as possible.

If a family jumps too quickly to discuss an ultimate resolution, it may miss essential steps in understanding the complexities of the problem. Instead, the family can be encouraged to start small, discussing and making decisions on seemingly minor issues. Minor decisions can be stepping stones to improved communication, mutual respect, and an agreement that will work for all because it was created by all. Among many approaches to small decisions, four deserve special attention:

1. Get Volunteers for Joint Homework

Two or three family members can agree to collaborate on “homework.”

SIDEBAR

FFI Mediation Virtual Study Group

This study group is a venue for FFI members with mediation skills to share developments in the field of dispute resolution through discussion of their practical experience, skill building, marketing, and other related matters. In addition to discussions among members, the group will host presentations by members and recognized thought leaders in various mediation disciplines, as well as related fields, including developments in psychology and neuroscience.

2. Make Small Decisions by Consensus

The family just described realized that, to accomplish those goals in a complex transaction, it needed experts in six distinct fields. Instead of having the mediator propose one expert in each area, the family was invited to make suggestions and, together with the mediator’s network, agreed to interview two experts in each area.

3. Write “DRAFT” on Every Document

An important technique is to label documents “DRAFT,” conveying that the advisor is not all knowing and needs help from family members. They improve the document, experience collaboration, and develop a sense of “ownership” of its contents.

4. Agree on “Next Steps”

Getting the family to agree on “next steps” is an important small step toward collaboration. A “next step” can be tacked onto a particular issue that needs research, or it can be as simple as agreeing on the next meeting.

The four techniques above can gradually build a sense that the family can shape its own future. Once stated, these approaches are almost self-evident – but their significance should not be underestimated.

Conclusion

Using the above approaches – probing for deeper concerns, encouraging a sense of togetherness in facing the problem, offering a conceptual construct to seek order in chaos, and nurturing the client’s own creativity – can produce exhilarating results. This is where the challenge of dealing with the emotionality of family conflict in the context of complex organizational issues can lead to the satisfaction of seeing a family celebrate a resolution they themselves created. Often some very simple approaches helped them get there.

References

1Fisher, R., Ury, W., & Patton, B. (2011). Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In (3rd ed.). Penguin Publishing Group.

2Associated Press. (2021, January 23). Larry King, broadcasting giant for half-century, dies at 87. The Boston Globe. Retrieved from https://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/01/23/nation/larry-king-broadcasting-giant-half-century-dies-87/

About the Contributor

Jack Wofford, FFI Fellow, is the 2022 recipient of the FFI Interdisciplinary Award. Jack is a mediator, facilitator, lawyer, and arbitrator with his own national and international practice based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He has practiced consensus building for over 40 years, beginning with major public policy conflicts, and continuing as partner in the real estate department of a Boston law firm, resulting in construction of complex development projects. From 1999 to 2002, he was a Presidential appointee to the Federal Service Impasses Panel, resolving disputes in negotiations between the federal government and its unionized employees. Jack is a former member of the FFI board of directors. He graduated from Harvard College, Harvard Law School, and Oxford University, where he was a Rhodes Scholar. Jack can be reached at johnwofford@earthlink.net.

View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.