View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.

Thank you to this week’s contributor, Maya Prabhu of the FBR Research Applied Board, for sharing her précis of “The Effect of Value Congruence Between Founder and Successor on Successor’s Willingness: The Mediating Role of the Founder–Successor Relationship” – an article that appears in the September 2019 issue of FBR. In the article, Maya summarizes the research’s key findings as well as examining practical implications of the research for advisors in the field.

As we know very well, leadership and ownership succession of the family enterprise from generation to generation is a complex process and as such can have high levels of failure. The reasons why it may be successful, or not, have been extensively studied by academics and practitioners in the field who have found that the successor’s ability and willingness to take over is a key influencing factor.

The Research

This study which is featured in the September edition 2019 of Family Business Review is a welcome piece of research for several reasons. Amongst them, first and foremost, it is because it is based on a study of Chinese Family Businesses and thus adds to the diversity and richness of research in the field. Furthermore, family businesses account for over 85% of business in China (Ren & Zhu, 2016), and it is estimated that a majority of them will embark on their succession journey in the next 10 years. This study focuses on Founder to G2 succession.

Secondly, as the authors point out, this study is the first to concentrate on the founder and successor as a duo or ‘dyad’, exploring a) the congruence in their values (meaning here ‘the moral compass that guides an individual’s decisions and interactions in social relationships’) and personal goals towards the family’s ongoing prosperity, b) the impact that this congruence has on the nature of their relationship as the two main characters in the succession process, rather than their points of view as individuals, and c) how this influences the successor’s willingness to take on family business roles and responsibilities.

The sample for the study was recruited from the Next Generation Societies in Shanghai and Zheijiang. They are voluntary organisations with around 200 members each run by members of G2 in family firms. 102 founder/successor pairs participated in the study. Most of the successors were male, college graduates, and were on average 26 years old; the founders were also mostly male, of an average age of 51 years and had completed high school. The authors tested for difference in outcomes in the founders based on demographic differences (gender, education level, age) and did not find any significant variances. They could not test this for the successors as they did not have information on the successors who were not working in the family business.

The authors utilise Social Exchange Theory to examine the relationships between the founder and successor and then empirically test the role of value (in)congruence and successor willingness. Social Exchange Theory helps explain how the give-and-take of social and material resources in human interactions can enable or restrict the participants in terms of power and influence and in achieving long and short-term goals (Blau, 1964). ‘Restricted exchanges’ are more specific and short-term in nature, featuring direct reciprocity or quid pro quo. These types of exchanges can bring clarity and are simple in relationship terms and can thus serve to reduce anxiety. In ‘Generalised exchanges,’ on the other hand, there is no expectation of direct reciprocity between the participants, and, in fact, the overall relationship is more important to the individuals than any expectation of a quid pro quo for what they contribute (Daspit, et al., 2016). Both these types of exchanges exist in family businesses and will, of course, influence the relationship between the founder and successor.

Now let’s get to the authors’ conclusions and how these conclusions can add to our understanding and actions in practice.

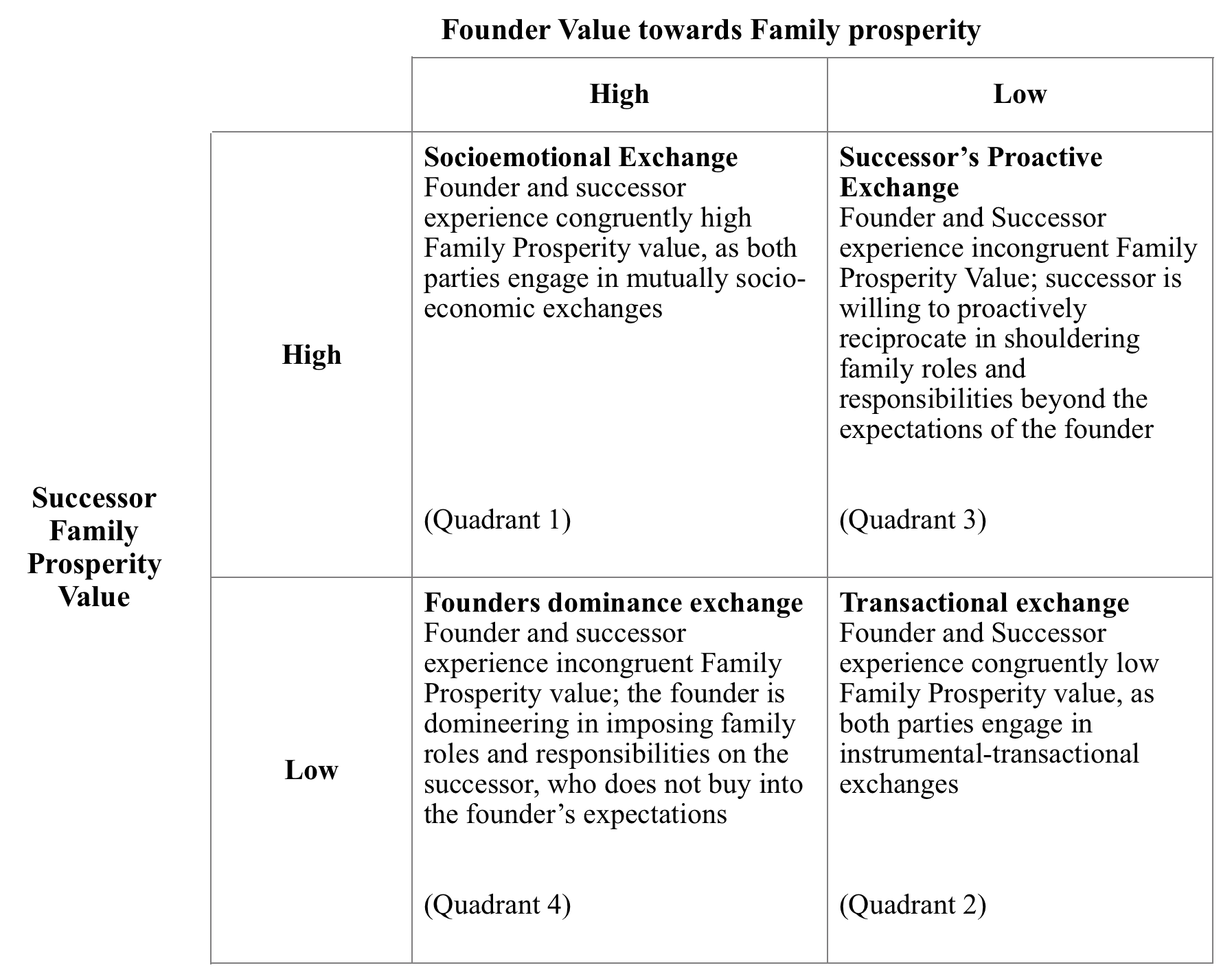

The authors employ the matrix below to describe their hypotheses about how the presence of value congruence (or not) can manifest itself, and the impact it has on successor willingness.

Figure 1: Source, Lee, Zhao, Lu, Family Business Review September, 2019

The Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1

What the matrix tells us in Quadrants 1 and 2 is that values between founder and successor can be ‘in sync’ when they have a high level of shared values and goals for family prosperity in the future, and also when they share a low level of interest in family prosperity. In case of the former (Quadrant 1), founders and successors will tend to enjoy more generalised social exchanges and work hard to build positive family relationships and a shared long-term vision. This alignment is often helped when the successor supports the founder’s vision (as this is chronologically likely to take shape first). This high value congruence then in turn gives rise to better information sharing, mutual trust, and collective decision-making. The founder in this situation also tends to feel more relaxed about ‘letting go.’

In Quadrant 2, on the other hand, the founder and successor may agree that they don’t individually or collectively share a long-term goal for their family business. They may build a consensus around their roles, which are more transactional in nature, looking more like restricted social exchange, and, as such, the quality of their relationship will not be as close as in Quadrant 1. For example, this may manifest itself as an agreement to sell the business and to pursue individual goals after that.

Hypothesis 2

Similarly, Quadrants 3 and 4 demonstrate that the impact of incongruence is also nuanced. When successors have a higher interest in family prosperity and the family business in the long term, they will tend to demonstrate their keenness to take on responsibility and to work hard. This ‘filial piety’ may overcome the founder’s reluctance to view the successor as a possible leader of the business in the future. The founders’ starting point may be that they don’t have faith in their successors, but while the social exchanges will not be warm, the hard work of the successor can mitigate the negative effects to some extent.

On the other hand, if the founders have a high orientation towards family prosperity, it is likely that they will insist on their long-term vision for the company to remain with the family and ‘force’ heirs to fulfil their wishes. However, the successor who has a low value for family prosperity may have his or her own goals, interests, and plans, and this lack of congruence will impact the quality of the founder – successor relationship as the successor will feel frustrated and unwilling to take on the roles that the founder wishes him or her to take on in the future.

Hypothesis 3

The authors tested a third hypothesis which is that the quality of the relationship between founder and successor can mediate the (in)congruence in their vision and value towards the future, and, therefore, the successor’s willingness to take on the succession responsibility.

Using numerous statistical tests including polynomial regression and response surface methodology, the authors tested and proved that their hypotheses are empirically supported.

Conclusions and Observations

Succession is such an important topic for us in practice. The model above in Figure 1 gives us a framework to understand and consider successor willingness, its influencing factors and impact; an important insight and knowledge that can be a resource for the families we support.

It gave me an insight into a family that I am currently working with. The founder and successor have a close family relationship of mutual respect, shared hobbies, and they enjoy spending time together. However, they have radically differing views (high value incongruence) on the future of their global business – on what the family’s role in relation to the business should be and also on the purpose of the business in the future (is it for the benefit of the shareholders or the benefit of the employees and community? You can probably guess who holds what point of view!). As a result, the successor said he was generally unwilling to play a part in the business in the future. However, due to their close father-son relationship, the successor is working hard and doing his best in the business even as they discuss and debate finding a middle ground or a different ground they can agree on for the future.

About the Contributors

Maya Prabhu, Managing Director and Head of Wealth Advisory for J.P. Morgan Private Bank, writes for FFI in a personal capacity.

Maya Prabhu, Managing Director and Head of Wealth Advisory for J.P. Morgan Private Bank, writes for FFI in a personal capacity.

About the 2019-2021 FFI UK/Europe Regional Planning Committee

The purpose of this committee is to expand the presence of FFI as an organization and the FFI members themselves in UK and Europe area in the coming years, to build enthusiasm for the 2021 October conference in London, and to promote the multidisciplinary, global approach that is at the core of FFI’s mission “to be the most influential global network of thought leaders in the family enterprise field.” As its first initiative, on September 24, the committee hosted a Master Class with Dr. Kris Verburgh in London.

This article represents the third in a series of FFI Practitioner articles from the committee members, following “The Role of Risk Management in a Family Enterprise” by Bilal Zein and “Behavioural Risk in Family Business: Some thoughts on individual stories” by Elizabeth Bagger.

View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.