View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.

This week’s FFI Practitioner continues a series of articles written by members of the FFI IberoAmerican Virtual Study Group that are available in both English and Spanish. Thanks to Miguel Angel Gallo and Begoña Pereira-Otero for their examination of what constitutes an appropriate exercise of power by family business owners. We hope you enjoy this article in either (or both) languages!

The responsibility of those that hold power in a business is to govern and manage the company so that it fulfills its social function as a community of people.

In the case of family businesses, the exercising of this power is vital: the owners of the business – usually a relatively limited number of people – make decisions for the future of the organization, hopefully keeping it viable for as long as possible.

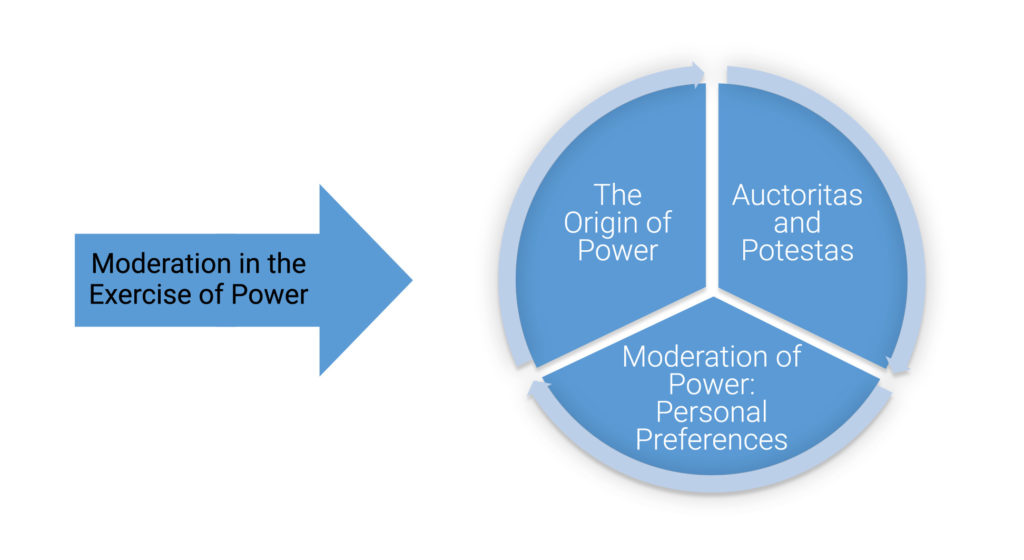

For this reason, it is necessary to determine if the exercise of this power is appropriate. But how does one do this? We believe that it is necessary to identify the origin of power, distinguishing between auctoritas and potestas, and to understand the personal preferences of those in control. Additionally, we advocate joint decision-making to moderate the exercise of power in the business.

The Origin of Power

Many owners of family businesses are convinced that the power is theirs because they founded, constructed, or inherited the business — sometimes these are the only factors they consider when regarding the origin of their power.

Moreover, these individuals often are convinced that they already possess the necessary skills for exercising power correctly, or that they will soon attain them – which is not always the case. (It is interesting to note that the exercise of power has an extraordinary attractiveness1 to all types of people.)

We should also point out that power always comes from someone, frequently delegated by someone that is socially recognized to do so. For this reason, we should always ensure that the ultimate objective of this delegation is for the common good.

From this perspective, knowing and willfully accepting the origin of power is necessary to understanding better who holds power in the life of a business and why. The owners of the business, and those that hold power within it, should consider themselves administrators and not owners. For example:

- administrators in the name of a community of people – they do not all have to be owners – which applies to all businesses, particularly the family business;

- administrators in the name of future generations, exercising power with professionalism; and

- administrators convinced that the business is not there to do whatever they want with or to make their will everlasting, like those that wish to rule after death.

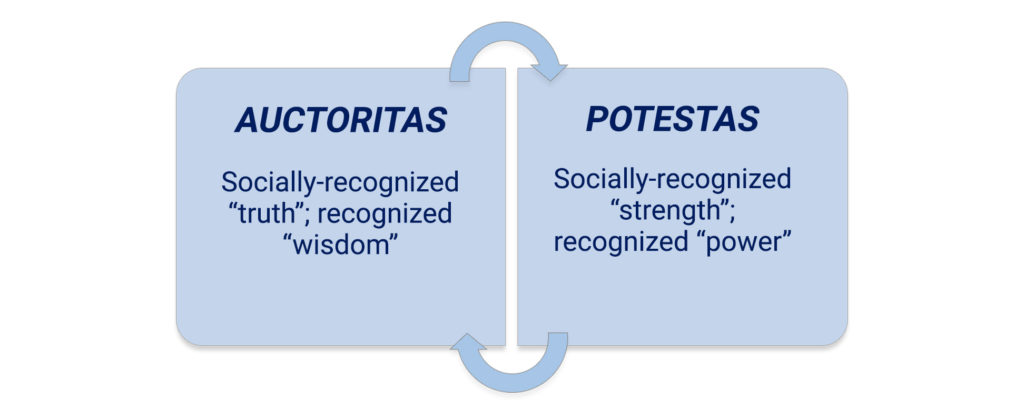

Recognition of Power: potestas and auctoritas2

Our understanding of the recognition of power is based on two concepts:

This recognition is key: without it, the auctoritas would remain pure wisdom and the potestas pure strength.

In the case of individuals that govern and manage businesses, their auctoritas, their knowledge, must be recognized by the members of the organization they represent, whether directly or by proxy. This recognition makes coercive power unnecessary. In fact, the core of true auctoritas is in its “renunciation” of force. It is completely different from paternalism, which acts as a “dictatorship of false love.”3

Potestas is frequently confused with coercive power, or “the capacity of an individual to configure reality in the way that best suits them, that best satisfies their desires.”4 This confusion, which can lead to false assumptions about the level of potestas that a person has in an organization, is difficult to hide over time.

So then, what is the relationship between auctoritas and potestas in the business? The functions of auctoritas are advice and control, while the functions of potestas are execution and direction for the achievement of goals. For this reason, the relationship between them, when it comes to governing and managing the business, should not be considered in opposition, but rather as a complementary relationship — the higher the level of auctoritas of the person governing the business, the greater the convincing strength of his or her potestas. We believe, therefore, that the best use of potestas is to know how and when to question and let one’s self be guided by the auctoritas, without trying to convert auctoritas into a mask for potestas.

Everything that we have discussed so far affirms the extraordinary importance of those that exercise potestas in the family business. Being the owners or future owners of its capital, they should strive to acquire the highest level of auctoritas possible. In the process of professionalizing the business, the accountable individuals should strike the greatest balance between auctoritas and potestas. Without this balance, elevated potestas with low auctoritas can lead to “tyrannical” behavior and/or lead pursuing strategies that are not in line with the individual’s skills or the performance of the business.

Personal Preferences

Full power is a scarce resource in a business and often those in control are unaware of their personal preferences and be subjected to the negative influence of their individual preferences, e.g., their appetites, aspirations, desires, inclinations, and values.

It can be said that in a business it is impossible, or at least very difficult, to formulate a “pure”5 economic strategy. It can also be said that the economic rationality of the individuals that govern and manage the business is limited6. This is not to say that biased rationality equates to irrationality7, but that biases can be limiting. The decision maker, when biased, is “skewed to one side”, and often does not learn more about other aspects at play, does not further elaborate his or her thinking, and does not make an informed decision…. or decides only based on personal preference. “Limits” in knowledge have a skewing effect, e.g., the individuals that govern or manage without seeing the bigger picture is inclined towards what they do know, perhaps incorrectly.

Moderation of Power: Joint Decision-Making

The points that have been presented have an extraordinary influence on the good work and continued success of family businesses. They lead to an important question: How does one help individuals that exercises full power and who want to reach optimal levels of auctoritas in the fulfillment of their responsibilities?

The answer to this question is multi-faceted. One of the most important ways is to help them develop a team of managers – both from inside and outside the family – that complement their abilities, which are determined by the balance between their personal levels of auctoritas and potestas, and by their coordination and integration skills.

Another important aspect is joint decision-making in the government of the business, as well as collaboration with subordinates, or any group of people that can moderate the full power of the decision maker. Joint decision-making is, to a degree, established in the legislation of capital companies. Such legislation defines extraordinary government – the general board – and ordinary government – the board of directors and single administrators. The diverse modes of operation of the administrators are detailed – especially of the ordinary administrators.

However, we want to point out that joint decision-making is characterized by two fundamental points: organizing a group for decision making and coming to a consensus as a group.

Organization of a group. The group will act as an ordinary governing body of the business. In some cases, it will coincide with the provisions established in the charter; in other cases, it may not be established legally, but the business decides to respect its decision. This group must be formed by an adequate number of people – even if they are not owners or members of the family – due to the complexity and size of the business; these individuals should all have equal standing, with qualities that complement the government of the business, and should be independent in their decision making and loyal to the community of people that is the business.

Coming to a consensus. This is the result of a process of deliberation during which the following concepts should be applied, especially by those that exercise potestas:

- Listen to the opinions of the other members of the group with the intention to better understand the reasoning behind these opinions.

- Present your own opinion sincerely and completely.

- Change your mind when the ideas of the other members of the group are better for the common good.

- Do not delay the decision unnecessarily, waiting for new ideas that may or may not come.

- Faithfully implement the group’s decisions, even if they are contrary to your opinion.

We firmly believe that those that hold full power in a business have the responsibility to govern and manage the business so that it complies with its social function as a community of people. We believe that this is possible only with the responsible exercise of potestas, an optimal balance of auctoritas, and the moderation of power through joint decision-making.

Bibliography

– ACTON. Carta del obispo Mandell Creighton, 5 de abril de 1882. Himmelfarb, G. (1972). Acton Essays on Freedom and Power, pp. 335-336.

– ALVIRA, T. (2005). Filosofía de la vida cotidiana. (3ª edición). Ediciones Rialp, S. A., Madrid.

– BARNARD, Ch. (1938). The functions of the executive. (6ª reimpresión). Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

– BURGOS, J. M. (2008). Antropología: una guía para la existencia. (3ª edición). Edificiones Palabra, Madrid.

– CHRISTENSEN, C. R., ANDREWS, R.P. BONER, I.L., HAMERMESH, R. G. and PORTER, M. (1982). Business Policy. Text and cases (5ª edición). Richard D. Irwin, Ind. Homewood, Illinois.

– CRUZ, J. (2010). “La familia como origen” en Cruz, J. (ed). Metafísica de la familia. (2ª edición). EUNSA, Pamplona pp. 121-139.

– DOMINGO, R. (1987). Teoría de la “auctoritas”. EUNSA, Pamplona.

– PÉREZ LÓPEZ, J. A. (2002). Fundamento de la Dirección de Empresas. (5ª edición). Ediciones Rialp, S.A., Madrid.

– POLO, L. (2007). Quién es el hombre: un espíritu en el tiempo. (6ª edición). Edidiciones Rialp, S. A., Madrid.

– TORELLÓ, J. B. (2010). Psicología y vida espiritual. (2ª edición). Ediciones Rialp, S. A., Madrid.

– VALERO, A. y LUCAS, J. L. (1991). Política de Empresa: El gobierno de la empresa de negocios. EUNSA, Pamplona.

– WOJTYLA, K. (2010). Mi visión del hombre. (7ª edición). Ediciones Palabra, Madrid.

– YEPES, R. y ARANGUREN, J. (2003). Fundamentos de antropología. (6ª edición). EUNSA, Pamplona.

– ZUBIRI, X. (1985). El hombre y Dios. (3ª edición). Alianza Editorial, Madrid.

Notes

1Read: Adler – en Torelló, 201, p. 76 (“power is the prince of instincts”); Yepes and Aranguren, 2003, p. 178 (“man has a tendency, propensity, and inclination, whether secret or manifest, to dominate others”); Torelló, 2010, p. 121 (on egocentric personalities “their only happiness is power…and their only pain is the loss of dominion, that is to say, dependence”); Alvira, 2005, p. 71 (“power is one of the three fundamental inclinations of human nature: the tendency toward power, the tendency toward recognition, and the tendency toward pleasure”); Acton, 1882, (“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely”).

2The ideas presented in this section about potestas and auctoritas are based on concepts developed by Álvaro D’Ors (Domingo, 1987).

3See: Cruz, 2010, p. 125

4See: Pérez López, 2002, p. 87

5“Those that formulate it, contaminate it” (see: Barnard, 1947, p. 12-45); “The diagnosis of a situation always has a subjective component…in the end, we are all wearing goggles” (see: Valero and Lucas, 1991, p. 49 and 72).

6See: Christensen et al., 1982, p. 363

7See: Burgos, 2008, p. 132 (“…feelings are different than logical rationality, which isn’t to say that they are irrational or that reason cannot or should not have anything to say about them, but that they are feelings and not reason”)

About the contributors

Miguel Angel Gallo, FFI Fellow, is professor emeritus in the Department of Strategic Management at IESE. He obtained his doctorate in engineering from the E.T.S.I.I., Barcelona (Spain). He has widespread professional experience, having served on the boards of management of prominent firms such as AVANCO, ANESIN, Widewall Investments and Grupo Senda (Mexico). He is president of the Family Business Consulting Group (Spain), Fand Honorary President of the International Family Enterprise Research Academy (IFERA). He is the recipient of the 2001 Richard Beckhard Practice Award.

Miguel Angel Gallo, FFI Fellow, is professor emeritus in the Department of Strategic Management at IESE. He obtained his doctorate in engineering from the E.T.S.I.I., Barcelona (Spain). He has widespread professional experience, having served on the boards of management of prominent firms such as AVANCO, ANESIN, Widewall Investments and Grupo Senda (Mexico). He is president of the Family Business Consulting Group (Spain), Fand Honorary President of the International Family Enterprise Research Academy (IFERA). He is the recipient of the 2001 Richard Beckhard Practice Award.

Prof. Gallo has published several books, such as The power in the business (2016), The future of the family business (2011), or Basic ideas for managing the family business (2008). He is co-author of numerous books (Keys in the family business advising (2016), The multigenerational family business (2009), Family Constitution (2006), etc.), and also published abundant journal articles and research papers. He can be reached at MGallo@iese.edu.

Begoña Pereira-Otero obtained her doctoral degree in Business Administration from University of Vigo -research distinguished with Honorable Mention in Best Doctoral Dissertation category by FFI (Academic Awards 2007)-. She is a Certificate Holder in Family Business Advising (CFBA) and has an MBA from IESIDE. Begoña is a faculty member at IESIDE and has a private practice in BPO Consultores, advising company specialized in governance, strategy and human resources. She is co-author of the book Keys in the Family Business Advising (2016), and also published several research papers. She can be reached at bpo@bpoconsultores.es.

Begoña Pereira-Otero obtained her doctoral degree in Business Administration from University of Vigo -research distinguished with Honorable Mention in Best Doctoral Dissertation category by FFI (Academic Awards 2007)-. She is a Certificate Holder in Family Business Advising (CFBA) and has an MBA from IESIDE. Begoña is a faculty member at IESIDE and has a private practice in BPO Consultores, advising company specialized in governance, strategy and human resources. She is co-author of the book Keys in the Family Business Advising (2016), and also published several research papers. She can be reached at bpo@bpoconsultores.es.

Miguel Angel and Begoña are co-founders of Club de Asesores de Empresa Familiar (Club AEF).

View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.