View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.

Thanks to FFI Fellow Guillermo Salazar, a member of the FFI Iberoamérica Virtual Study Group, for this article that explores the relationship between the hero archetype and storytelling in family enterprises. This article continues the series of bilingual editions by members of the FFI Iberoamérica Virtual Study Group and you have your choice of reading it in English or in Spanish!

For people in the family enterprise consulting world, the analysis of a business family’s shared narrative helps them understand their clients and the shared realities they have built. Understanding the language of family mythology and the behavior of narrative processes can help positively transform the purpose of the legacy and the meaning of its transmission to future generations.

Family businesses that foster a culture of intergenerational connections and a long-term vision include a robust set of family values and stories to pass on to future generations.1 It is my perception, from my consulting experience, that enterprising families frequently build their own stories based on the hero archetype.

In his 1949 work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, anthropologist Joseph Campbell proposed the term monomyth as a universal mythological structure, applicable to all societies or groups of individuals that have built, over at least three generations, a collective identity. Palo Alto researcher Antonio J. Ferreira2 coined the term “family myth” as a unitary representation, a homeostatic mechanism, that maintains group cohesion and prevents the family system from deteriorating and eventually destroying itself. During the 60s, Murray Bowen noted the specific patterns of behavior transmitted through innumerable generations, defining the psyche as the result of all the chronological conditioning factors surrounding it. For Jung, the unconscious was partially collective, but for Bowen, the conscious and unconscious was collective. In this article, the hero’s journey will be examined more closely as it relates to family enterprise consulting3.

The Hero’s Journey

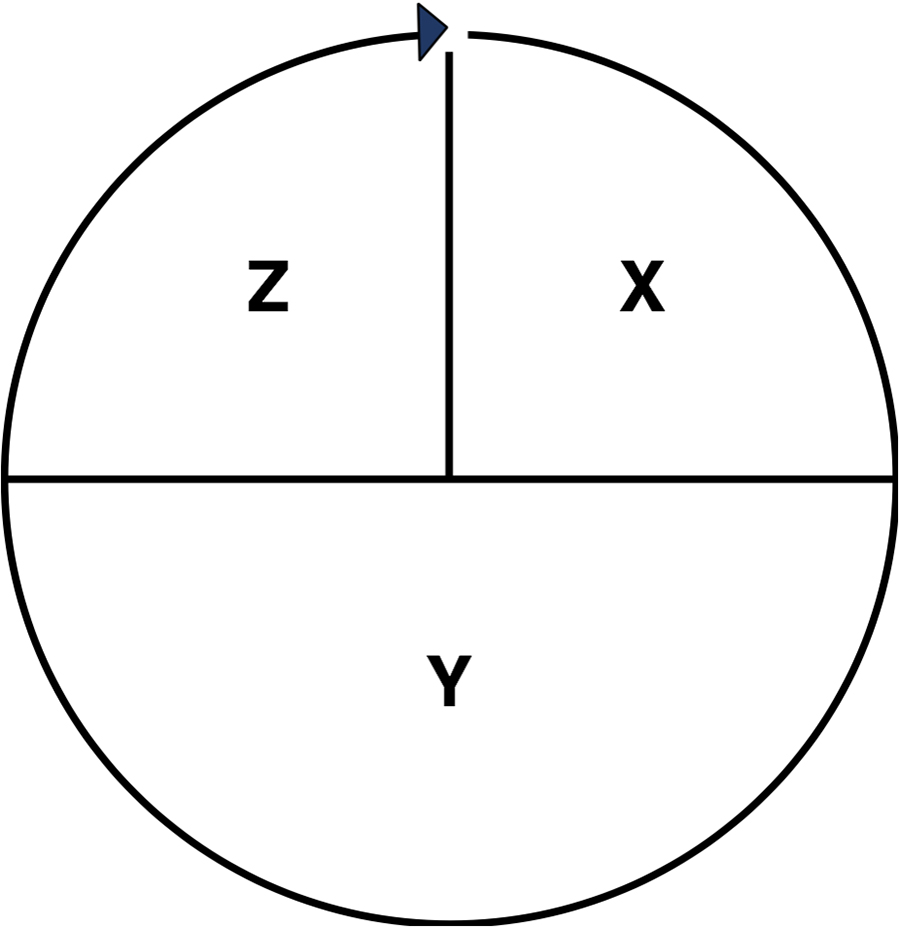

In the hero monomyth, Campbell describes the hero based on the route he takes through the different stages of a journey, transforming him from an ordinary person into the bearer of justice for his community. There are three primary stages or acts of narration: separation from the world (X), penetration to a type of power source and the return home (Y), but with a new life (Z).

At the start of the monomyth, the hero is an ordinary character who undertakes an extraordinary journey following a “call” (which he initially rejects) to enter an unknown world, full of mysterious powers and characters and strange events. Once past the threshold that separates him from his home world, the hero will face different tasks and tests, either alone or with help. However, there is one crucial test that the hero must complete to overcome death and receive a reward. Once completed, the hero must decide whether to return to the ordinary world with the obtained gift.

If the hero chooses to return, he will face new challenges on the way back to the ordinary world, including acceptance (or not) by those who have not left their original world. If his return is triumphant, the hero uses the blessing or reward to improve people and bring justice.4

The Monomyth Nuclear Unit (Campbell, 1949).

Making Conscious the Unconscious

Building family storytelling helps order and give coherent meaning to the family story and its message and values, as most of the structure of family business narratives (especially businesses in second- and third-generation stages) is based on the myth of the founder. Beyond the cohesive functionality of legend-making in the family system, the creative capacity of these stories allows one to make sense of reality and build a meaningful future.

From a neurological point of view, the machinery that relives the past is the same that simulates the future.5 Understanding and acknowledging the past proposes a way to validate the entire human experience and paves the way for creativity and flexibility. According to FFI founder and Richard Beckhard Practice Award recipient, Ivan Lansberg, “as a species, we are too limited to imagine a world we don’t know much about.”6 This inclusive and exploratory approach reveals countless avenues for better relationships, less conflict, and a more efficient way of working as a group.

FBR Associate Editor, Peter Jaskiewicz7 confirms that only recently have researchers studying highly innovative family businesses revealed that a shared family and business history passed down from generation to generation can positively influence the level of family business innovation. Stories with a strong focus on past achievements and resilience passed on to subsequent generations foster transgenerational entrepreneurship. This ability to document directly depends on the ability to listen. In reconstructing a shared past, compassionate and empathetic participants, with the capability to question and express curiosity, even about a painful past are vital. Interviewers and listeners need to commit to preserving memory and participating in the dynamic of the narrative, and this is not always possible.8 That is why family business advisors have an essential role as guides to the creative process that is both moldable and healing. In Campbell’s words, “A myth cannot be artificially created or destroyed, but it can be modified.”

In the results of their studies, FBR Associate Editor, Nadine Kammerlander, et al.,9 demonstrated that shared stories can serve as essential means of transmitting and preserving the founder’s story from generation to generation (“second-hand impression”). Interestingly, interviewees in Kammerlander’s research mentioned that the core of the stories shared among family members remained mostly stable over time; however, each generation enriched the transmitted stories, thus gently altering their content. As storytellers are responsible for a shared legacy, each family can transform the myth and feed a group image of their past, an “arranged,” “mythical” story, which highlights an ancestor with particularly heroic behavior.10 A focus on shared stories lends legitimacy to a broad spectrum of decisions, empowering family members of each generation with the motivation to commit to the long-term success of the company and overcome obstacles.

Storytelling, in general, allows advisors to provide enterprising families with learning that remains impressed on their consciousness using their own words. It is not the experience of life itself, but the meaning the family gives it. “The secret is: know yourself (know your family!)”11. The utility of the hero’s journey as a healing tool is based on the power of the monomyth that has supported civilizations for millennia, and that connects both advisors and clients to deep internal problems, internal mysteries, and rites of passage.

References

1 Denison et al. And Rothstein, citados por Labaki et al., 2012. Emotional dimensions within the family business: towards a conceptualization. Artículo de “The Handbook of Research on Family Business (2nd Edition)”. Cheltenham, UK. Páginas 734-763.

2 Ruffiot, André (1980). La función mitopoiética de la familia: Mito, fantasma, delirio y su génesis. https://www.psicoanalisiseintersubjetividad.com/website/articulo.asp?id=266&idd=8.

3 Stinson, Patrick (2016). Jung was ‘Thinking Systems’: A Juxtaposition of Jungian Psychology and Murray Bowen’s Family Systems Theory. PSY 7174 History & Systems of Psychology. California Institute of Integral Studies.

4 Existe una conexión entre el mito del héroe y el modelo del emprendedor como agente de cambio. En algún momento de su extenso trabajo, Campbell llamó al empresario el “verdadero héroe” en la sociedad capitalista estadounidense. Ver Morong, Cyril (1992). The Creative-Destroyers: Are Entrepreneurs Mythological Heroes? Presentado en el Western Economic Association Meetings en 1992 en San Francisco, CA, EEUU. https://cyrilmorong.com/CreativeDestroyers.pdf

5 Seekamp, David (Ed.) (2019). The Mind Explained: Memory. Documental original producido por Netflix. S1E01. 20 minutos. Scotts Valley, CA.

6 Lansberg, Iván (2020). What do the owners want? How business families think about their future. Trusted Family Webinars. Bruselas, Bélgica. https://trustedfamily.net/insights/2020/1/31/what-do-the-owners-want-how-business-families-think-about-their-future.

7 Jaskiewicz et al. (2015), citado por Kammerlander, Nadine et. al (2015). The Impact of Shared Stories on Family Firm Innovation: A Multicase Study. Family Business Review. Vol. 28(4) 332–354. Sage Journals. New York, NY.

8 Jelin, Elizabeth (2001). Los trabajos de la memoria. Siglo XXI de España Editores. Madrid, Spain. 146 pp.

9 Kammerlander, Nadine et. al Op cit.

10 Ruffiot Op cit.

11 Fokker, Loes (2019). The Role of Storytelling in Aligning Family and Wealth. Trusted Family Webinars. Brussels, Belgium. https://trustedfamily.net/insights/2019/8/1/the-role-of-storytelling-in-aligning-family-and-wealth

About the Contributor

Guillermo Salazar is the founder and managing director of Exaudi Family Business Consulting. Guillermo is a lecturer, educator, author, and expert advisor on family governance, strategic succession planning, generational transition and conflict resolution. He is an FFI Fellow, former FFI board member, and a former member of the GEN (Global Education Network) faculty. Guillermo is the recipient of the 2015 FFI International Achievement Award and was the chair of the 2019 Global Conference Program Committee. He can be reached at guillermo.salazar@exaudionline.com.

View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.