View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.

In this week’s FFI Practitioner, FFI Asian Circle Virtual Study Group member Nelson Lam addresses the challenges that can emerge in family enterprises when the successor is the family’s only child, as is the case for those born in China during the country’s one-child policy. Lam discusses the work of psychologist Edgar Schein and that of wealth advisor and FFI Fellow James E. Hughes, Jr., and he suggests how advisors can use their work with client families.

For many contemporary Mainland Chinese families, the transition of wealth and leadership across generations is shaped by a defining demographic legacy: the successor is the only child. A result of China’s one-child policy (1980–2015), this reality has created a generation of heirs raised without siblings—each bearing the full weight of familial expectation, emotional investment, and dynastic continuity.

While having a single heir simplifies succession on paper, it introduces profound psychological, relational, and governance challenges. With no siblings to share responsibility, compare capabilities, or provide balance, the family enterprise often becomes caught in a dyadic system—a high-stakes, emotionally charged, one-on-one relationship between the parent and only child.

In this context, decision-making lacks structure, governance is rarely formalized, and power dynamics are deeply personal. The founder may delay relinquishing control out of concern for readiness; the heir may feel overwhelmed by duty yet disempowered in practice. Cultural values such as filial piety (孝, xiào), hierarchical respect, and emotional restraint often prevent open dialogue about succession, capability, or even the heir’s true aspirations.

The result is a fragile system:

- Succession is assumed, not prepared.

- The heir is labeled “the successor” without being given real authority.

- Professional management is resisted, as trust is reserved for blood.

- There is no alternative successor, increasing systemic risk.

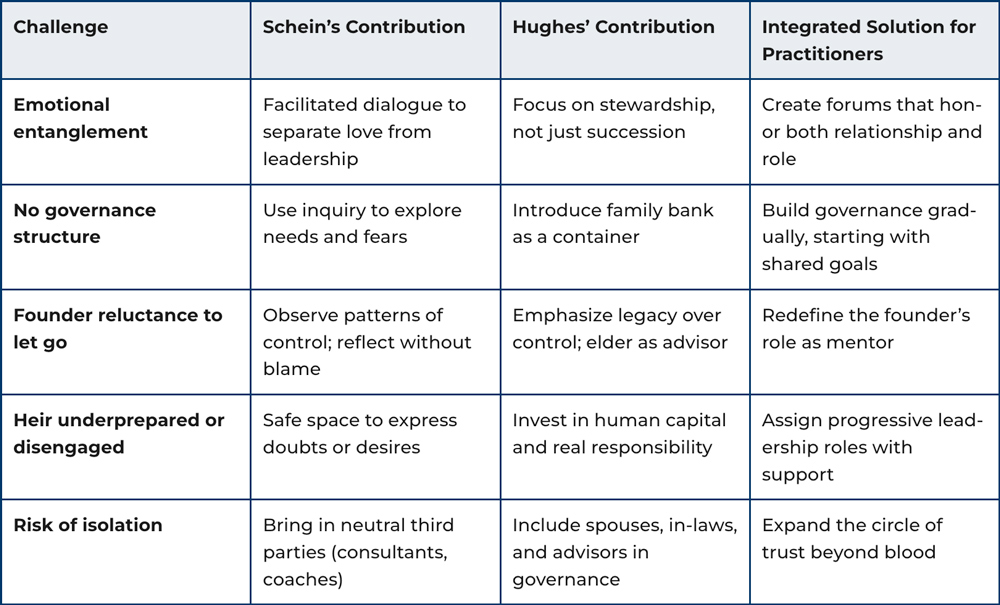

To navigate this, Chinese families need an advisory approach that is relationally intelligent, culturally grounded, and developmentally paced. Two frameworks offer exceptional synergy: Edgar Schein’s process consultation1 and James E. Hughes’ philosophy of family wealth.2 Together, they provide a path to transform the parent-child dyad into a structured, multi-generational stewardship model—preserving harmony while building resilience.

Two Guiding Frameworks: Schein and Hughes

Edgar Schein, an MIT organizational psychologist, pioneered process consultation—a method that prioritizes inquiry, observation, and empowerment over prescription. His approach excels in culturally sensitive settings, helping families see their dynamics clearly without triggering resistance.

James E. Hughes Jr., a leading voice in family wealth, champions a holistic view of prosperity. He argues that true legacy rests on four pillars: financial, human, intellectual, and social capital. For families with a single heir, his emphasis on stewardship, long-term vision, and inclusive governance offers a path beyond mere succession.

Together, their philosophies provide a balanced foundation: Schein helps families understand how they interact, while Hughes helps them envision who they want to become.

I. The Challenge of the One-on-One Dynamic: Governance Without Structure

In families with multiple children, governance emerges naturally through comparison, negotiation, and shared responsibility. But when the only child is the sole heir, these dynamics vanish. Decision-making becomes personalized, unstructured, and opaque, often reduced to private conversations between parent and child.

This may create several risks:

- No succession timeline: The founder may retain control indefinitely, with no clear transition plan.

- No development path for the heir: The child may be seen as “next in line” but is not prepared for leadership.

- Emotional entanglement: The heir is not just a future leader but also represents the emotional legacy of the parent, making objective evaluation nearly impossible.

- Lack of governance mechanisms: Without siblings, there is no natural council, no forum for dialogue, and no buffer between generations.

In this context, governance does not emerge organically. It must be intentionally designed, not as a Western import, but as a culturally adapted structure that supports clarity, growth, and continuity.

II. Edgar Schein’s Process Consultation: Creating Space for Reflection in a Dyadic System

Edgar Schein’s process consultation is uniquely suited to the emotionally charged, high-dependency relationship between a parent and the only child. Rather than imposing external models, Schein’s method helps families observe their own patterns and develop their own solutions through inquiry, feedback, and facilitated dialogue.

1. Inquiry to Surface Unspoken Assumptions

Open-ended questions gently disrupt unexamined beliefs:

- “What does it mean to you that your child is the only one?”

- “What would it feel like if your child led the family office differently than you?”

These questions invite reflection, especially in a culture where succession is rarely discussed directly.

2. Observation of Relational Dynamics

A consultant may observe common patterns in client family dynamics:

- The parents speak for the child in meetings.

- The heir defers even when asked for an opinion.

- Emotional reactions (e.g., guilt, pride) override strategic discussion.

By neutrally describing these patterns—“I noticed that whenever the son began to speak, the father completed his sentence”—the consultant helps the family see how their relationship shapes decision-making.

3. Creating Third Spaces for Dialogue

Schein emphasizes the need for neutral, facilitated conversations, separate from business or family meals, where roles can be explored safely. These “third spaces” allow for new conversations:

- The parent and the child can both express their aspirations and fears freely.

- Both the parent and child can explore succession as a shared journey, not a transfer of power.

4. Building Awareness Without Blame

In a face-conscious Chinese culture, direct criticism is avoided. Schein’s non-judgmental feedback preserves dignity while fostering change:

- “It seems the family trusts only those with the family name. How might that affect access to expertise?”

III. James E. Hughes’ Philosophy: Reimagining the Only Child as Steward, Not Just Successor

James E. Hughes, in Family Wealth: Keeping It in the Family (2004), reframes wealth as more than financial assets. He emphasizes four forms of capital:

- Financial

- Human (individual growth)

- Intellectual (shared knowledge)

- Social (relationships and trust)

For families where the only child is the heir, Hughes’ philosophy is transformative. It shifts the focus from “Who will take over?” to “How do we prepare this person to steward a legacy?”

1. Human Capital Development

As the only child, the heir has likely grown up with limited experience in negotiation, compromise, or peer accountability. Hughes advocates for education and guidance:

- Mentoring and coaching

- Global exposure and cross-sector experience

- Psychological resilience training

This aligns with the Confucian ideal of self-cultivation (修身, xiushen): the belief that leadership begins with personal virtue.

2. The 100-Year Mindset

Hughes encourages families to think beyond the next generation:

- Preparing not just for their leadership, but for his/her children.

- Establishing rituals, values, and education funds that outlast any individual.

This long-term vision helps depersonalize succession and reduces the pressure on the heir to “be everything.”

3. Family Bank

Family bank—a dedicated fund for education, entrepreneurship, or philanthropy—can serve as a governance catalyst and create structure for implementation of practices such as the following:

- Regular family meetings

- Decision-making practice for the heir

- Involvement of in-laws or trusted advisors

It transforms the heir from a passive recipient into an active steward.

4. Inclusive Governance Despite Singularity

Hughes emphasizes that governance does not require multiple offspring. Even with the only children, families can create councils with elders, spouses, and independent advisors to provide wisdom, balance, and continuity.

IV. Integrating Schein and Hughes: From Dyad to Dynasty

The integration of Schein and Hughes offers a powerful pathway for families with the only child as heir to evolve from a fragile one-on-one system to a resilient, institutionalized family enterprise.

V. The Broader Context

As a generation-wide phenomenon in China, millions of “only children” heirs, raised under intense parental focus and societal change, are stepping into roles as sole stewards of wealth, identity, and continuity.

This cohort shares common traits:

- High academic and performance pressure

- Strong parental attachment

- Limited experience in shared decision-making

Understanding this context helps advisors anticipate challenges and design support systems that go beyond the individual family.

VI. Conclusion: From Inheritance to Stewardship

For Chinese families where the only child is the heir, the greatest risk is not financial loss, but the collapse of governance into a personal, unstructured, and unsustainable relationship. The one-on-one dynamic, while intimate, lacks diversity of perspective, the natural checks and balances that support long-term continuity.

Schein’s process provides the relational tools to help families see their dynamics clearly and talk about the unspeakable—fears of failure, desires for freedom, and dreams of legacy.

Hughes’ philosophy offers the visionary framework to reframe the only child not as an inheritor, but as a steward of human, intellectual, and social capital across generations.

By combining Schein’s facilitative wisdom with Hughes’ generational foresight, families can transform their offices into enduring institutions—where harmony, legacy, and wealth are not preserved by control, but cultivated through intention, dialogue, and shared purpose.

References

- Schein, Edgar H. Helping: How to Offer, Give, and Receive Help. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2009.

- Hughes, James E. Family Wealth: Keeping It in the Family: How Family Members and Their Advisers Preserve Human, Intellectual, and Financial Assets for Generations. Bloomberg Press, 2004.

About the Contributor

Nelson Lam is a family office executive with 10+ years of experience building and managing a full-service single-family office. His expertise spans governance, operations, compliance, financial management, and team leadership. He founded Chronicle Advisors, an independently owned multidisciplinary platform, whose mission is empowering the growth of family offices in Asia. He can be reached at nelson@chronicle-advisors.com.

View this edition in our enhanced digital edition format with supporting visual insight and information.